The Village Where Everyone Keeps Punching Themselves in the Mouth

by Michael Conley

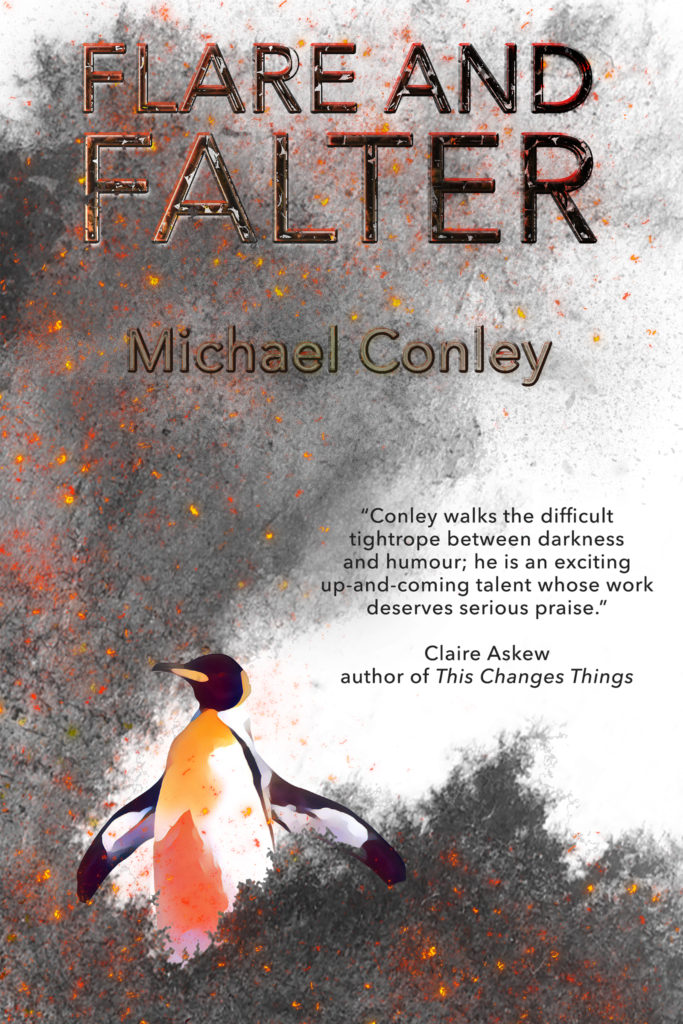

A new short story by Michael Conley, author of Flare and Falter, published exclusively online.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

The guys in the office laughed when you were assigned this one. You’ll know them by their scabbed knuckles, they said, by their clawed right hands cradled always at chest level like twitching beach-rescued starfish.

And they won’t tell you anything.

You start with their Wikipedia page. There’s surprisingly little on the whole ‘punching themselves in the mouth’ issue. You have to scroll right down to the heading at the bottom: ‘Controversy’:

In late 2016, the media reported extensively on an “epidemic of self-harm”[1] supposedly “sweeping” the village. Although the stories were on this occasion sensationalist in tone and largely exaggerated, many were correct to note that there is a long-established and widely-misunderstood tradition of the cultural practice of mouth-punching that has always been observed by residents of this area of the country.[citation needed]

No further explanation and nothing at all on the rapid spread of the practice over the last eighteen months.

The rest of the page is less than useless, written with the pedantry of the kind of amateur local historian who will no doubt head straight for you in the pub on your first night. There are several paragraphs on the village’s medieval origins, a section on the successful protest against the construction of a sand quarry in the late nineties, and a list of every single bus, with numbers, that travels to the slightly larger towns dotted throughout the region. There’s even a section entitled ‘Notable People’, although it consists of only a single name, an archery bronze medallist from the Rio Olympics in 2016.

“They’re so weird about that archery guy, as well.” You jump at the sound of the voice so close to your ear. Arkley is standing behind you, reading over your shoulder. You hate it when she does that. Arkley scouted out the village a year and a half ago, when the first reports trickled in. You should probably schedule some sort of debrief with her, if you want to play this by the book.

You minimise the Wikipedia tab and turn to face her. “What do you mean?”

She takes a bite from her foil-wrapped breakfast burrito. A drupelet of scrambled egg plops onto your keyboard. “Everyone under thirty claims they were in his class at school,” she says. “He lives in London and has never been back. And listen to this: after he picked up his bronze medal, the village painted all the postboxes gold even though Royal Mail specifically asked them not to.”

You don’t reply. She pats you on the shoulder, almost sympathetically. “You’ll love it there. Have a good time.” She swaggers away, chuckling.

You spend the rest of the morning in the archives, looking through Arkley’s reports, which is almost as bad as spending time with her. You wince at every spelling mistake, every homophone error. They are so frequent that you suspect she probably went back into the files last night and planted them all there just to irritate you.

You’ve been in the job way too long to be idealistic any more. You’re not going to get to the bottom of this. You’re going to stay in a B&B just outside the village for the maximum three nights it will take you to write your report, and then you’re going to leave.

Still, that first night in the pub does shock you with its unpleasantness, despite your natural detachment and the details in Arkley’s reports that were supposed to make you feel prepared. You walk in and endure the obligatory stranger-entering-a-saloon moment. All conversations fall into silence and every face turns towards you. But then the impact of this moment is ruined by the fact that it seems to coincide with an ‘everyone-punching-themselves-in-the-mouth’ moment. They’ve been doing this so long now that their cycles appear to be fully synchronised and they all do it at the same time so that the wet thudding squelch is amplified, like the noise of a muddy football kicked hard into a naked belly. Arkley had told you they don’t hold back, and she wasn’t kidding. Many of them make a little whimpering noise and try to hide the pain with a discreet wince, like people pretending to not hate the taste of whiskey. Some wipe tears from their eyes, and then they all continue as though nothing at all has happened.

Ever the professional, you inconspicuously place your hand in your pocket and start the stopwatch on your phone. Arkley was curious to know whether the punch cycle had changed from the twenty-six minutes that elapsed between episodes when she had been there to observe the village. You order a pint of warm ale, sit in a corner, and exactly seventeen minutes later, you get your answer.

You send Arkley a quick text message. She replies: “Knew it would’ve shortened. And their all doin it now, arnt they?” They weren’t all doing it when she was last there; she’d observed that it was mostly the over-fifties, but there are definitely some younger people in here tonight. You confirm it for her. “Knew it,” she replies, with a smiley-face emoji.

Later in the evening, your prediction comes true and you are approached by a grey-haired, moon-faced man in his early thirties. He looks you directly in the eye and, through split lips like a dropped lasagne, he demands to see what you’ve been writing in your report. He seems happy enough when you buy him a drink instead. He takes out his own special straw so as not to spill it. He is definitely the person who wrote the Wikipedia article.

“I expect you’re going to be asking why we do it?” He is still staring at you, his expression of defiance made clownish by the mess of his face. You sigh.

“Nope.” If he is disappointed by your answer, he disguises it well.

“We’re not going to tell you why we do it.”

“Okay.”

“I expect you’re going to advise us to stop doing it.” There is a pause. Unexpectedly, he gives your shoulder a weak shove. The shove is weak because two of his fingers are broken. “Go on, advise us to stop doing it.” A couple of older men sitting at the bar tense up, studiously pretending not to listen.

You roll your eyes. “I’d advise you to stop punching yourselves in the mouth. It’s not good for your health.”

He stands up and, despite being only twelve minutes into the new cycle, he gives the side of his own chin a shockingly robust whack. You hear his teeth click together and a glob of bloody saliva improves the pattern on the wallpaper.

“We don’t need you to tell us what’s good for us, city mouse.” He talks like a man with too much porridge in his mouth. He looks down at your own unbroken fingers disgustedly, as though he can’t stop picturing you using them to caress your own soft private parts.

The two men at the bar have turned around and are openly watching you now. In unison, they begin a loud, slow handclap. Then, one by one, all of the people in the pub rise to their feet and join in the applause. The Wikipedia man remains standing over you, his open palms turned upwards, his long arms held out in a wide shrug. You finish the last of your pint and leave. As the door swings shut behind you, you hear a cheer.

Back at the B&B, Arkley sends you a text message just as you’re falling asleep.

“Enjoying ur self? Bought u sum shares in knuckle plasters and Bonjela.” There are three crying-laughing emojis appended to it, along with, unaccountably, a trumpet.

“Why the trumpet?” you ask.

Arkley does not respond, even though it says she’s read the message.

The next day you spend some time walking around the shops, such as they are, on the village’s high street, such as it is. You are surprised at how quickly you’ve adjusted to the normality of the bruised and beaten faces of everyone you encounter. You suspect that when you get back home, you’ll have to get used to seeing unblemished mouths again. The postboxes are a muddy, rusty hue: off-red, if such a thing exists.

There’s a charity bookshop, full of the brightly-coloured ghost-written autobiographies of wankers. In a stationery shop, a woman in a floral print blouse, with lips like the thighs of a balloon poodle, insists loudly to the cashier that she can distinguish between people of different races by smell alone. In Waitrose, three people separately take you aside to tell you that the homeless man outside isn’t really homeless, and that you should put that in your report, front and centre. To each, you explain that your report isn’t really about homelessness, and each replies with the same, “Well, it wouldn’t be, would it?”, along with an expression which, on a normal face, might convey triumphant disgust.

When you get outside, you ask the homeless man if he’s really homeless, and he tells you politely that he is. He in turn points to two teenagers across the road, kicking a football lethargically against a wall. He describes the young people around here as “feral.” You cross the road and ask them if they are feral, and they tell you politely that they are not.

At the end of the street, you find a hardware supplier who seems to promise a miscellany of household items. You are especially intrigued by the neatly set-out row of individual boxing gloves, in various sizes, displayed prominently in the window. The glass in the bottom half of the front door has been smashed and replaced with fibreboard.

You step into the premises. The shopkeeper looks up from a copy of The Daily Express spread out on a benchtop.

“Isn’t that cheating?” you ask, nodding at the display with a wide smile that you hope conveys your light-hearted intent.

The shopkeeper becomes immediately defensive. “I’m just providing a service,” he says. “I’ve got to make a living. I don’t want any trouble.” You notice that, unlike many of the other people you’ve seen today, his mouth reveals extensive bruising but no broken skin, no swelling or scabbing. You notice that although his left hand is resting, too casually, on the keypad of the till, he keeps his right hand under the counter, out of sight.

“Do many people buy the gloves?” you ask, more seriously this time.

The man twitches. “I don’t have to share my customer list with you,” he insists. “It’s a private matter.”

You nod, pensive now, and force yourself to smile. The man doesn’t smile back. You leave. Later that day, when you Google the name of the shop, you’re bombarded by page after page of one-star customer reviews spiked with words like “Judas,” “saboteur,” “cock,” and even a couple of direct death threats.

There is no message from Arkley. In the absence of anything else to do, you touch yourself to completion. Unbroken fingers, yes. That night, you sleep soundly.

You wake the next morning with the sun already out and decide to take a wander through the park. A young family approaches the play area. The man and the woman have their arms around each other’s waists. Their little girl, who looks to be five or six, is eating a strawberry ice cream. Her hat has little mouse ears on top. She darts ahead to sit on a swing.

The stopwatch on your phone vibrates in your pocket, and, on cue, the mother and father both punch themselves hard in the mouth, splitting their own lips again, then they exchange pleasant, bloodied smiles. You watch the little girl. She holds onto the chain of the swing with her left hand while she grips the ice cream in her right. You can see her working through the calculation, slowly, slowly. Finally she smashes the ice cream into her face. No blood, but still lots of red.

You feel tired and, for the first time, you sense a wave of anger. It doesn’t quite hit you full force, not yet, but you can feel it threatening, like the pregnant air before a storm. You force it out of your mind. The mother wipes the child’s face with a tissue that sticks to the ice cream in patches of shredded white. The father puts the ruined ice cream in the bin with an expression on his ruined face like the approximation of a frown. You wonder if these people love their children as much as you would love yours, if you had any. You force that thought out of your mind, too.

Later that afternoon, you stop the car on a country road to watch a farmer building a stone wall. His lips, like everyone else’s, are horribly swollen; a cigarette dangles from the corner of his mouth. You step out of the car and rest against the bonnet, lighting your own cigarette. The man gives you an almost imperceptible nod, then mashes his fist into the red flesh around his lips without wincing.

“Building a wall?” you ask.

“Yep.”

“Good fences make good neighbours, eh?” He doesn’t respond, not even with a polite grunt or any hint of having recognised the reference. “Need any help?”

“Nope.”

You watch him with care as he picks his way along the edge of his field, in search of the perfect stones for his wall. You are receptive, in your own mind, to some sort of epiphany. There is no doubt that this man has this land in his veins, his bones. He can probably identify every single one of his sheep by sight. You marvel at his conservation of energy; he barely moves his head as he lets his eyes scan the field for rocks exactly the right size and shape to fill the gaps in the wall, then he makes a beeline for them. He’s like a chess grandmaster, thinking ten, twenty stones ahead, and there is a confidence and grace in his long strides as he picks up stone after stone, weighing each in his large right hand and placing it delicately, patiently, into a wall that will never win any prizes for beauty but will no doubt outlast the pair of you. You lose all track of time until you realise that your cigarette packet is empty and you’ve been watching him for nearly an hour. You give him a brief wave, though you’re not even sure he really sees you, and then you climb back into the car and drive away.

You’d been so distracted that it only strikes you later that his punch cycle was off: twenty-six minutes, not seventeen.

Arkley’s message on your final night here reads “upd8?” along with an emoji with a wide open smile.

You don’t really know what to reply, so you text back: “when you came here, did you look into the history of it?”

You wait at least half an hour before your phone pings with a new message: “did i fuck.” For some reason, you imagine Arkley saying it through a mouthful of breakfast burrito.

You sleep in past your alarm the next day and incur an unreasonably large fine from the B&B for checking out ten minutes late, rather than at eleven sharp. Driving back into the village, you pass by the same spot where the farmer spent yesterday working on the wall. There has been some bad weather overnight. The wall is nothing more than a pile of rubble and you have to swerve to avoid the corpse of a sheep in the middle of the road. You punch the steering wheel in frustration.

The public library is a squat brown building on the edge of the main residential area. Even though you should really be driving home, and you told yourself you wouldn’t get sucked in, you want to check the village’s records: you’re troubled by Arkley’s lack of curiosity about where this behaviour came from. You’re positive she’s missed something crucial. The librarian silently watches you struggle to locate the local history section. A group of three teenagers, whom you recognise as the ones you briefly talked to yesterday, are huddled around the room’s only computer. Every time they get too loud, the librarian shushes them, although through her bloated lips the shush becomes a wetter sound, with a ‘p’ and an ‘f’ in it. They seem to understand regardless.

The only other person in the library is an old man, sitting at one of the tables. He’s wearing a suit, but a faded one: dark grey, probably originally black. You feel the prickle of his eyes on you as you walk past, and when you look at him, he beckons you over like an old friend.

He’s got a piece of paper and a pencil, and a box of chicken bones. When you look down at him, he quickly curls his body over the paper, blocking your view.

“What are you drawing?” you whisper, in the absence of any obvious explanation for why he wanted to speak to you.

He looks up at you as though seeing you for the first time. “You,” he replies.

“Why?”

“Got to draw something.”

You pause.

“Can I see?” you ask, leaning in. He hunches further over his work.

“No.”

You look over at the librarian, who rolls her eyes. The pencil scratches on the paper.

“Can I at least see it when you’ve finished?”

“No.”

“What are you going to do with it?”

“Not telling you.”

The teenagers laugh. The librarian shushes them.

“Stop it,” you say, a little too loud. “I don’t give you permission to draw me.”

The old man stands up, pushing the piece of paper onto the floor. He places the pencil in his top pocket, the box of chicken bones under his arm, and leaves without looking back.

You reach down to pick the piece of paper up. On the piece of paper is a rectangular block of italicised circles, all rendered perfectly, like this:

OOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOO

You ball the paper up and put it in your pocket.

There’s a microfiche reader in a small room off to one side. You don’t bother asking the librarian’s permission to use it. You scroll through archived pages of the now-defunct local newspaper, not knowing exactly what you’re looking for. You keep scrolling patiently, as face after broken face clunks past in photographs of ever-decreasing quality. You’ve reached the late 1990s when you start seeing people with no disfigurements. There’s an article about the village’s successful case to oppose the construction of the sand quarry, in which at least half the people’s faces are completely uninjured. And then, after that, nothing: there are no archived documents at all from before that date.

You don’t know what use that is. You go back into the main library. The librarian and the teenagers seem to have set aside their differences: she’s standing with them at the main window and they’re looking at something outside. They don’t notice you. According to your stopwatch, their punch cycles are fourteen-and-a-half minutes. Quicker than the average. You don’t know what that means either.

You join them at the window. They’re looking at your car, which is on fire.

What does it mean? you wonder, as you watch the thick black smoke escape from the sides of the bonnet like ugly gossip. What does it mean that the punch cycles get longer and shorter? Does the interval vary depending on proximity to the cause, like the aftershocks of an earthquake? Do the time differences signify the existence of some central point, like an epicentre, where the cycle recurs every five minutes, or thirty seconds? Or zero seconds? Why does it vary from place to place?

The flames spread to the inside of the car, cracking the windscreen and consuming the leather seats. Then they flicker down to the front left tyre, which catches and explodes, just in a small way, but enough to make the librarian and the teenagers jump back from the window.

You could, through trial and error, and careful observation, walk around the local area and try to figure out the maths. You could find out whether there is an epicentre, and, if so, where it is and what’s there. If you wanted to.

“That’s your car, isn’t it?” one of the teenagers asks you. You ignore him and decide to head in the direction of where they didn’t build the sand quarry.

You’ve walked the length and breadth of the village, slowly, and it’s dark by the time you reach a patch of scrubland that stands away from the main estate. It’s deserted. There’s a chain-link fence surrounding a medium-sized building; small pieces of colourful fabric have been threaded carefully through the holes so that you don’t really have a good view of what’s inside. There’s barbed wire at the top and a chunky padlock on the gate at the front.

You’re just wondering whether you could climb over the fence, or otherwise force your way through, when you hear a car approaching. You slip around the corner of the fence, so that you can see the people in the car through the breaks in the colourful fabric, but they can’t see you. As the car pulls up, you see two young men inside. Each man’s face is an unholy mess, and even from here you can tell that they’re both punching themselves with an incontinent regularity and ferocity that you find truly shocking. You try to time the cycle. Two or three seconds, at best. If there’s an epicentre, this has got to be the place.

The young man in the passenger seat gets out quickly, runs to the boot of the car and takes out a large sack, all the while swinging wildly at his own face, so indiscriminately that he doesn’t even connect every time. The man in the driver’s seat, making the same wild gestures, yells at his partner to hurry up.

The first young man unlocks the gate quickly and throws the sack inside. As he’s fumbling, you make a split-second decision and spring out from where you are crouching. You tackle him before he can replace the padlock and you hold him down in the dirt, pinioning his arms. Behind your back, you hear tyres screech as the car roars away.

The young man is struggling beneath you. He’s already screaming and crying, you suspect more because he’s being prevented from hitting himself than for any other reason. He begins to hyperventilate. His right arm snakes out from between your two bodies, and before you can stop him he punches himself so hard in the temple that he knocks himself out.

You dust yourself off and step through the open gate.

Children. Maybe thirty of them. All pre-adolescent. Not hitting themselves. A mixture of boys and girls. There is a sleeping area, a kitchen area, a bathroom area, and it’s relatively clean and tidy, all things considered. They seem surprised to see you. It’s cold in here, and many of them are shivering. Damp air, concrete floor. You try to speak to the children but none of them seem to understand English.

The eldest, a girl of about twelve, warily skirts past you, towards the large sack that the young man dropped off. She drags the sack into the centre of the floor. The children crowd around it as she empties it to reveal enough Marks & Spencer’s ready meals to last them all week, along with some clean clothes of various sizes and even some expensive-looking toys. The children share the contents of the sack, quietly and politely.

You use your phone to take the necessary pictures. You send them to Arkley, along with the location.

It’s pitch black when you step outside. This time, though, the quality of silence is different and instinctively you remain still. When you look into the blackness, you can just about make out some darker shadows, clustered together a distance away. When you switch on the torch on your phone a gunshot rings out. You feel the displaced air from the bullet waft close to your head. You duck down and kill the light.

One by one, phone lights like yours switch on: a forest full of winking fireflies. The entire village must be out here, everyone crowding together on the edge of the scrubland. Between you and them, there’s empty space about the length of a football pitch. But even from here, and even in this patchy light, you can see that the punch cycle is disturbingly short. That’s why they won’t come any closer, you guess, unless they want to end up like the young man out cold on the ground.

Suddenly you hear the crackle of a voice bleating into a megaphone.

“WE HAVE HAD TO MAKE SOME VERY DIFFICULT DECISIONS.”

Hard to tell, but you’re pretty sure it’s the man from the pub on your first night in town.

You sigh. This sort of thing was exactly why you didn’t want this assignment in the first place. Why did you have to get involved? Remember when you told yourself you’d just get in and get straight out again?

“IT’S NOT A CAGE. IT’S A FENCE,” he insists, as though you had suggested otherwise. You remain perfectly still in the dark, wary of the guns.

There’s a scuffling sound through the megaphone, then a different voice. A woman’s voice: “WE DIDN’T HURT THEM.” The voice has the sound of pleading in it.

Thankfully, in the distance, you hear the helicopters approaching.

The first thing you do when you get back is thank Arkley for calling the authorities so quickly. Then you ask her out. Why not? She smiles and places her hand lightly on your bicep as she leans in and whispers in your ear, “Not if yours were the last unswollen lips on earth.”

You become a national hero, of sorts, briefly. There’s widespread public disgust at the imprisonment of the children, although it is noted that none of them spoke English and that the people of the village probably treated them better than their most likely feckless and irresponsible parents.

After much of the fuss has died away, Nick Robinson sits down on the Today programme for a chat with the man from the pub, along with a woman from Amnesty International, for balance. The man from the pub makes his case very calmly.

“One day you’ll look back and thank us,” he claims. “We tried lots of other things, but this was the only method that got results. This was the only way to stop it from spreading.”

“To stop what from spreading?” Robinson asks, genuinely puzzled.

“We have a right to keep ourselves and families safe and happy,” the man from the pub replies. “And your listeners’ families safe and happy. You’re only looking at this from one perspective, Nick.”

The microphone condenser deadens the thud of his fist into his mouth. Robinson turns to the woman from Amnesty International and asks her whether she thinks that the man from the pub has the right to keep his family safe and happy. The woman from Amnesty International says something about the inexcusable violation of moral limits. The man from the pub audibly tuts. Robinson thanks both of his guests for their time and hands over to the news at the top of the hour.

You flick off the radio and bite into your morning apple as you browse, incognito, job vacancies. It’s an unusually large bite and as you chew, you glance down at the apple, clutched so tightly in your clawed left hand that the tips of your fingers are white. You study the apple’s newly exposed flesh. There are several small pink splotches, crushed berries on snow, where the apple has made contact with your bottom lip, which you hadn’t realised was bleeding. Your jaw aches..

About the Author

Michael Conley is a writer from Manchester. His poetry has appeared in various literary magazines, and has been Highly Commended in the Forward Prize. He has published two pamphlets: Aquarium, with Flarestack Poets, and More Weight, with Eyewear. His prose work has taken third place in the Bridport Prize and was shortlisted for the Manchester Fiction Prize.