Marked

by Michael Conley

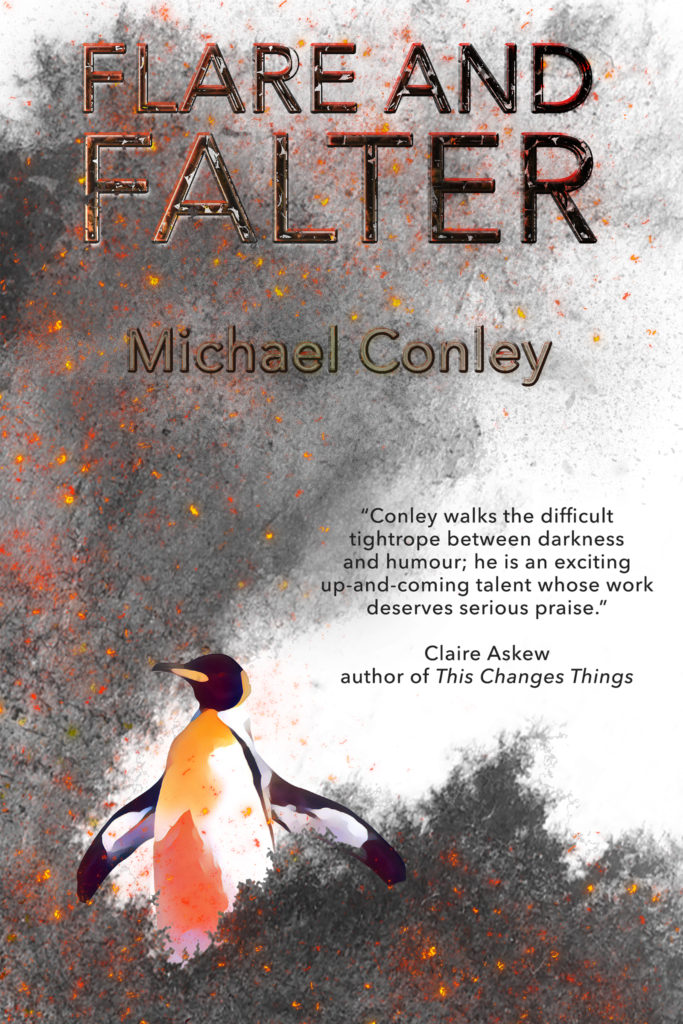

This story appears in Michael Conley’s Flare and Falter, available now from Splice.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

One night, Alphabet fell from the sky. It began with uppercase Y’s spinning earthwards past our bedroom windows like giant maple seeds. We heard them burst as they hit the pavement, spilling out millions of tiny lowercase versions of themselves, which caught on the wind and settled on footpaths and driveways and on tiled roofs. By the time we got to our door, the air was already a ransom note: supersonic streamlined V’s shot by with their white-hot tips, while seabird W’s and M’s wheeled on the currents and fat water-melon O’s bounced off car bonnets.

It wasn’t just our letters either: afterwards, some swore they’d seen hieroglyphics tearing nimbus clouds to cirrus, or Hebrew characters entwining with Cyrillic and tumbling together, backlit by moonlight. When the debris landed on our skin, it was cold, but not at all unpleasant. At dawn, the first punctuation appeared. Children ran around, catching exclamation marks on their tongues.

By seven in the morning, it was over. We were all out in the streets in our pyjamas, looking up open-mouthed as the last few commas fluttered about our heads. The panic only began when we realised that the ink covering us from head to foot was indelible. Rumours circulated about similar scenes in Paris and New York.

The press, at a loss to explain the origins of the attack, instead focused on the human interest. Some newspapers were certain that people had been given the messages they deserved, citing the iron-fisted drug lord who’d been laughed off the estate by his subjects when they discovered TURNIPS planted in a circle on his bald patch. Others lamented the random cruelty of it all and wheeled out the grandmother who now refused to leave the house because of the way F, C, and K had been arranged around a U-shaped birthmark on her chin. The Archbishop of Canterbury called it “irrefutable evidence of a divine presence” but nobody listened, since we were watching a dozen altar boys slopping soapy water over the ten-foot high NULLUS DEUS scrawled across Westminster Abbey.

A well-known right-wing demagogue, who blamed terrorists for the new Arabic tattoos on his forearms, had some success by scrubbing the letters pink with wire wool, but his wild-eyed triumphalism was short lived when they returned in the scar tissue.

Post-mortems found traces of ink in bone marrow. Scientists declared that it had turned our DNA to Blackpool Rock.

Some got away with quotations from Shakespeare, Plath, Seuss. Two or three were imprisoned for displaying state secrets. Comic Sans started their own social justice group, claiming unfair treatment from the rest of us.

That year, it was all anyone talked about, until it wasn’t. Life crept back to normal. When the first post-attack babies were born marked, it became clear that this was now a part of us, and we got on with the same old business as before: falling in and out of love, winning wars, losing wars, murdering, tweeting, marrying, going bankrupt, becoming celebrities. Strange: it never occurred to any of us to see what would happen if we were all to stop and stand side by side, and then start to read.

About the Author

Michael Conley is a writer from Manchester. His poetry has appeared in various literary magazines, and has been Highly Commended in the Forward Prize. He has published two pamphlets: Aquarium, with Flarestack Poets, and More Weight, with Eyewear. His prose work has taken third place in the Bridport Prize and was shortlisted for the Manchester Fiction Prize.