Michael Conley

In Conversation

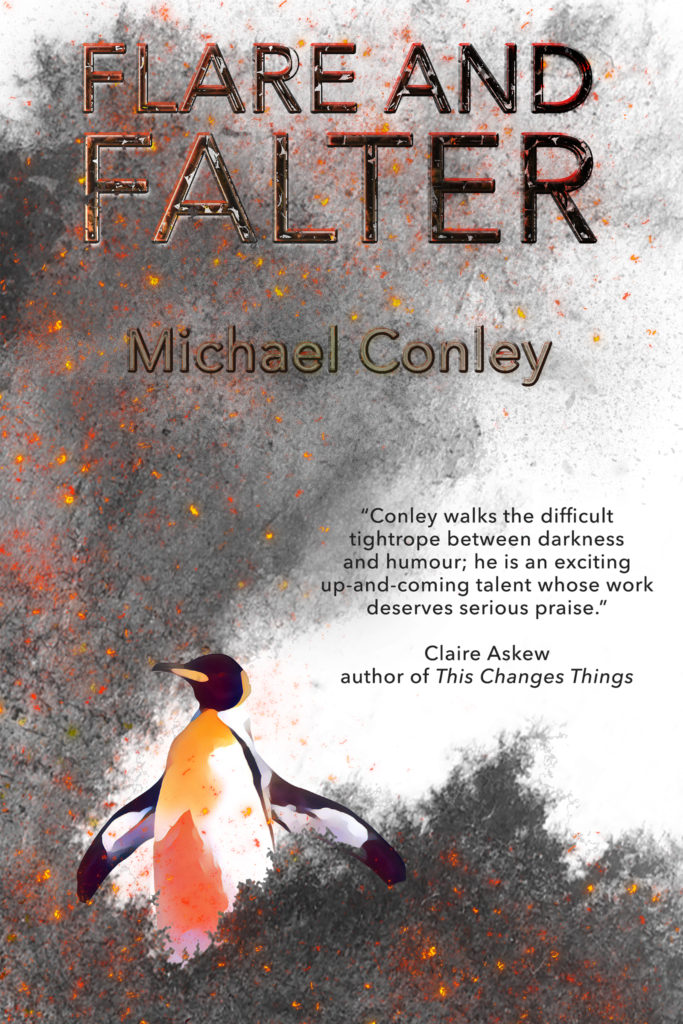

Daniel Davis Wood speaks to Michael Conley about his story collection Flare and Falter.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

So you’re officially a poet who has made the transition into prose, although you’ve been working on prose for a few years now. What was it that prompted you to try your hand at prose? And in general — thinking back to very early stories like ‘Anatidaephobia’ and ‘The God Quetzalcoatl’ — what rewards and challenges have you found in the process?

Both of those early stories you mention, along with the vast majority of the shorter stories in the collection, actually started out as poems that I couldn’t make work.

I originally had ‘Anatidaephobia’ written out in four-line stanzas, each of which had two short first lines followed by two much longer lines, which was supposed to resemble a side-on duck’s head, because I was amused by that idea as a stupid visual joke in a poem about a man haunted by a duck. But then the long lines got so long that they collapsed, and it basically turned itself into a piece of flash fiction.

With ‘The God Quetzalcoatl’, that one started as a series of about seven or eight poems that I wrote, all snapshots of Quetzalcoatl’s life in the pub. I had them for a long time because I liked the idea, but I ended up having to be honest with myself that none of them were very good as poems individually. They didn’t quite have the intensity to stand by themselves. So the transition to prose in that instance, I guess, was just a case of stitching the moments in the poems together like a kind of patchwork.

What about the more recent stories?

Since January 2018, when we started talking about publishing this book, I’ve worked very hard and intensively and probably been writing much more regularly and voluminously than I’ve ever done before. I’ve felt it’s been kind of a crash course. With prose I’ve enjoyed having much more breathing space structurally: ideas can be developed more slowly, and it’s been freeing to be able to disregard things like rhythms, line breaks, stanza breaks.

But the other side of the coin is that, if you’re not careful, a lack of formal restrictions can make you less creative with language. Plus, you’re shaping something much bigger, and you can lose control of it more easily, and you have things like pace and dialogue to consider instead. Having said that, it’s important not to overstate the differences between approaches either. It’s still just putting the right words in the right order, in the end.

That’s interesting to me for a couple of reasons. The first reason is that you did an MA at the Manchester Writing School, a pretty illustrious programme at Manchester Metropolitan University, so I guessed you’d at least dabbled in prose while you were there. Was that not the case? What kind of stuff did they have you doing?

I did do a little bit of prose writing while I was there, but at MMU there’s a poetry route and a prose route, and they tend to keep them pretty separate. I did one elective on Crime Fiction, which I enjoyed because it taught me a lot about plotting and genre writing. But that’s what I saw it as — an exercise in learning some things about how to write that way — and the prose I actually wrote at the time probably wasn’t good enough to do anything with. And anyway, I was just more interested in learning about poetry and writing it, at that time.

So how did the instruction you received at MMU actually end up shaping your work?

I just saw the whole process as a huge privilege. I’m aware of how lucky I was to be in a position to do it, for a start; I’m a teacher and I did it part-time. Some of my favourite moments just involved being in a room with a handful of other people who loved literature and valued writing as much as I did. From conversations I had with those people, both in and out of the seminar room, I learned a lot about writers I’d never heard of — some of whom are now favourites — and about the wider UK literature scene, and where to send work off for publication.

I remember I started the course thinking I was well-read, and then speaking to others and realising very quickly, with panic, that I wasn’t. So the first thing I learned was to read way more and engage more with current writing. All writing is part of a wider cultural conversation, so you have to hear what others are saying before you can contribute anything of real value.

What about the workshop process, group critiques, that sort of thing? Useful or not?

I enjoyed it. It helped me to see my writing as a piece of work I’d done that I could let go of, rather than a little piece of my soul that I had to guard from criticism. It taught me that producing ‘bad’ writing does not automatically make you a fool or a bad writer, and that doing so is not only inevitable, but maybe even a necessary part of the process of producing ‘good’ writing. But the best things I learned from doing the MA were all personal and developmental, rather than specific instructions or writing techniques or anything like that.

Actually, that ties into the other thing that I find interesting about what you said regarding your work in prose. If I can put it this way, your stories seem to be liberated from received ideas about what constitutes ‘good writing’ and ‘bad writing’. It’s not like the language is ever sloppy or that the structure is loose — far from it — but that they have this quality of wild abandon to them, like a flagrant and conscious disregard for conventional notions of neatness.

I know that in my chats with you, I’ve compared some of your stories to the work of Donald Barthelme. I don’t mean to make the comparison in a lazy way, as shorthand for absurdism, but really to point out similarities in that deadpan tone and the lopsided structure you find in Barthelme stories like ‘I Bought a Little City’. Those things are right there to a similar degree in some of your stories, particularly ‘The Superhero Your Rotten City Deserved’ and ‘Rory’s Difficult Year’. There’s a Kurt Vonnegut vibe sometimes, too…

I do like Donald Barthelme a lot, and I like your phrase “a flagrant and conscious disregard for conventional notions of neatness.” Anyone who’s seen me try to wear a suit for a wedding will recognise that. I take your comments here about wild abandon as a huge compliment. It’s a quality I’m always excited to find as a reader: my favourite writers are ones who do unpredictable and even confusing things.

I guess what I mean is that there’s no sense, ever, that you’re working with some of the narrative and stylistic templates you tend to find in creative writing classes. Every story is its own particular beast, and it feels like it has come into the world with no anxieties about how its shape matches up with other stories. How much of this feeling is something you’re deliberately aiming to create, and how much is more the product of spontaneity and speed? Going into a new story, on the first draft, do you give a lot of thought to the ways in which you can make it different to everything else, or is this something that happens along the way?

The two best books I’ve read in the last year or so have been George Saunders’ Lincoln In the Bardo and Leone Ross’ Come Let Us Sing Anyway, both of which I loved because they took you with them, but never made you feel entirely comfortable from one page to the next. I read Ross’ book especially at a time when I was working on a lot of the stories in this collection, and it was like a shot of creative energy: “Oh, stories can twist this way, or can be doubly effective by being doubly shorter, or can end abruptly like this.” Eley Williams’ Attrib. did a similar thing.

On the other hand, with some of the stories, I used poems as touchstones: for example, ‘All the Little Yous Just Find Each Other’ came from a line in a James Wright poem about bursting into blossom, and ‘Pinniped’ was inspired by Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘At the Fishhouses’, in which Bishop describes the taste of the sea as like “what we imagine knowledge to be”. I had both of those poems in front of me almost the whole time I was writing those stories, as inspiration.

So I suppose that doing unusual things with stories isn’t something that I set out to do deliberately when I start, because it’s the ideas that come first. But it’s certainly an effect I want, so I don’t think it’s entirely due to spontaneity either. I wonder if it’s also something to do with not deciding straightaway whether what I’m writing is a poem or a piece of flash fiction or a longer short story. I feel like that approach maybe opens up some avenues structurally, or in terms of perspective, which might otherwise be closed off too early.

One particular thing I’d say is that you’re very, very good at working in two quite different modes of writing, and sometimes reconciling them. You’re great at intermittent structure, using section breaks to make a narrative jump ahead in time — a day, or several days, or weeks — and then just slyly indicating some of the incredible things that have happened in the interim. And you’re great at orchestrating an ‘us versus them’ dramatic conflict that builds tension through events on the periphery of the action: rumours and hearsay, heckling, naysaying, all of which erupts into something more serious.

I don’t know whether you find it easy to write in these two modes, or easier than writing in a more conventional mode, but most writers I know find this stuff hard. It’s hard to maintain the momentum of a narrative when you keep chopping up its structure. It’s equally hard to maintain the tone of a conflict when you don’t focus on the participants and really take time out to develop their psychologies. And yet, you make it look like a breeze. If you’ll allow me to get technical, I’d say that you maintain the momentum and the tone not by amping things up with the structure or the conflict, but by throwing in oddball details at regular intervals. The reader is urged to read on, I think, not because he/she is wondering what will happen next, but because he/she doesn’t know what’s coming next at the level of the sentence and in the imagery.

Thoughts?

Yes, what you’re saying about the power of oddball details and sentence-level surprises is exactly what I aim for every time I write something. It’s interesting that you say other writers sometimes find it hard to structure stories like this. For me, maybe because I’m used to writing these weird little semi-narrative poems, it feels easier, yes. As I said, I think my two touchstones at the moment are George Saunders and Leone Ross; Ross’ book really inspired me, and I think Saunders is the master of the oddball detail, which is why I find it exhilarating to read his sentences. Plus poets like Thomas Lux and Selima Hill do that too, and they’ve always been big influences.

Well, those two are now on my to-read list. We should add, for your readers, that the title of the collection, Flare and Falter, has poetic roots…

It’s a line from ‘The Armadillo’ by Elizabeth Bishop. She’s probably my favourite writer. I wanted to keep the title loosely linked to ideas around entropy, which you mentioned during the editing process, foregrounding entropy as a thematic link between the stories. This one stood out for me one afternoon as I was looking through Bishop’s Collected Poems.

Yeah. It was so unexpected, or it came from such an unexpected source, and yet, as soon as you put it out there, it felt right.

Poetic inspirations aside, what about your political inspirations? Or, more accurately, your literary political inspirations? A lot of your stories are very political — not in a Jonathan Coe state-of-the-nation satire kind of way, but more in a Dario Fo angry rhetorical farce kind of way. I’m wondering who you might take your cues from in that regard?

In literary terms, less Coe, more Fo, correct. Perhaps somebody in the middle of those two is Terry Pratchett, whose Discworld novels had a huge impact on me as a child. I read them all from the ages of about eleven to eighteen. There’s definitely anger in them, but that anger bubbles away beneath the surface. I think I also picked up from Pratchett that, if the human condition can be boiled down to anything, it’s probably incompetence. At the same time, though, acknowledging this shouldn’t involve a turn towards empty mockery or nihilism. The anger should stem from frustration or disappointment, but never hatred. There’s a fine line there. I like political writers who highlight absurdity but also angrily uphold the almost unreasonable expectation that we can all do better.

After Pratchett, as I got older, I discovered Vonnegut doing something similar, and also Margaret Atwood. They’re writers who play the important role of the child at the end of ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ going: “Everyone just hang on a minute…” I suppose the problem now is we’re seeing emperors who can manage to make a virtue of their nakedness and then convince just enough people that the child is a sneering elitist. So what do political writers do post-Trump? I guess we’ll find out, won’t we?

Sure, assuming there’s such a thing as a post-Trump era. We might not make it out.

One more topic to ask you about, before we talk about the collection itself. You submitted some of the stories in Flare and Falter to competitions like the Bridport Prize and the Manchester Prize, and you had some success. How do you think this affected your development as a prose writer? Were you surprised that your prose could catch judges’ attention?

Yes, I was definitely surprised, although I suppose I only tend to send things off if I’m proud enough of them that I think they’ve got a chance. Like all writers, I’ve had way more work ignored or rejected than anything else. But I don’t know if success in competitions affects writing development. Competitions are fun and exciting, and it can be a nice feeling to be materially rewarded for your work, with a prize or with recognition, but other than that…

Did you ever receive any real feedback from the places you submitted to?

I’ve received general feedback from judges’ reports, and the Manchester Fiction Prize was nice because there was a ceremony and a meal afterwards, so I got some feedback verbally. But — and this is the teacher in me coming out now — most feedback is, by nature, summative, not formative. It’s “I’m the judge and this is what I liked about what you did” rather than “this is a working document and here’s what you could do better”. So, in that sense, it isn’t directly affecting my development. That’s probably as it should be, too: it’s probably not good, when writing, to be too concerned with doing the sorts of things that will grab competition judges’ attention, at the expense of serving the ideas as they come.

Okay, then, we should take a look at the cumulative result of all those ideas. There are thirty-five stories in Flare and Falter, and they arrived at different stages, in different batches, written in different ways. Let’s start with the ones that were there from the very beginning.

Towards the end of last year, you were independently working on a collection of short stories and you already had a bundle. Most of these early stories were flash fiction pieces, and more than a few of them have ended up in Flare and Falter. I count only two that clock in at over 1,000 words, and the majority hover between 500 and 750 words. Some haven’t changed much throughout the editing and redrafting process, but some are quite different and probably more expansive. Looking back on these stories in light of the longer work you’ve produced more recently, how do they strike you now?

I think that core of stories for me represents a point at which I thought I had some prose worth publishing. As I said earlier, I’ve spent the last few years seeing myself only as a poet, but throughout that time I’d been putting aside ideas that didn’t quite work as poetry and keeping them in their own folder. In a way, that process meant that those stories had already been through a kind of editing in the sense that I’d already thought a lot about the precise language in them and about how they worked or didn’t work structurally. At some point last year, though, I started realising that the folder was getting bigger and bigger, and things I sent off from it were starting to be accepted by magazines and win prizes.

It feels like faint praise to say that they exist because they failed as poems, but it’s true, and that doesn’t have to be a value judgement. In fact, when I first put them together into a manuscript, I wanted to play on that idea so I entitled the collection An Inferior Art Form. And I thought it would be funny to have a bio that read “Michael Conley has published two collections of poetry and one collection of prose: An Inferior Art Form.” But I don’t actually believe that they’re inferior, and maybe the title isn’t that funny.

Anyway, I think that at its best, flash fiction, or prose poetry, or whatever you want to call it, does bridge a gap between poetry and prose. Lydia Davis’ work is a good example: her very short pieces are as disorientating and elusive as good poetry. Or, more recently, the pieces in Lucy Corin’s 100 Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses. They have the sort of snapshot, non-narrative quality associated with poetry, but without the visual and rhythmic formal constraints. Poetry clothed as prose, maybe? Or poetry that’s let itself go? I’m not sure if that makes any sense at all. At any rate, those early stories you mention are probably my attempt to try to inhabit that ground.

Are there any stories in the original batch that didn’t make the cut, though you wish now that they had?

Yes, there are more. But no, I don’t wish they’d gone in. If they’re not there, then it’s because they didn’t work or didn’t fit, and it’s important to be brutally honest. I have a folder on my desktop entitled ‘Not Good Enough’, which contains a larger proportion of writing than all my other folders — and it feels right that that’s the case.

So, then, the next batch of stories you wrote were the ones like ‘Amok’ and ‘To Armour a Vehicle’: a little longer than the others, more plot-driven, more eventful, and not included in An Inferior Art Form. It feels to me as if there was a leap, or a level-up, rather than a gradual progression, between what you were doing earlier on and what you were trying to do after you completed the first iteration of the collection. Would you agree with that?

Yes, I recognise this. I think it goes back to what I was saying about feeling a bit of freedom from the constraints of poetry. I sometimes feel when I write poetry that I’m trying to keep plot and narrative at bay. And because I was writing these, as you say, in a kind of period where there was no pressure on them, I suppose they did feel like me trying out something new. Definitely ‘To Armour a Vehicle’ feels a bit transitional, now that I look back at it — but hopefully still interesting as a piece.

Why does that story in particular seem transitional to you? Do you mean that you see it as having limitations which you’ve now exceeded?

Not exceeded as such, because I don’t really see it exclusively as a process of improvement, more a process where I explored different methods of expressing things. And ‘To Armour a Vehicle’, in particular, is a longer piece than a poem but it still doesn’t have as much narrative as the later ones, which are more expansive. I suppose it has things in common with a dramatic monologue, and maybe that’s why I see it as something that bridges the gap between the poetry I was used to and the plot-driven stories I wrote later.

I guess another transitional period began with the writing of the ‘Body Double’ stories. For the uninitiated — which is mostly everyone, since the book isn’t out yet — these four stories all revolve around the same protagonist, a hapless fellow in a faltering dictatorship who works as the body double for a tinpot tyrant. Each story finds the protagonist in a different scenario, although each scenario blurs the lines between honour and degradation. This guy is aware that he enjoys a rare privilege, being so close to the seat of power, and yet, in practice, his ‘privilege’ involves debasing himself in various ways, for the amusement of his boss, with no way to refuse, or even to quibble, and in fact with a real eagerness to please.

These stories came about through an interesting process. You wrote one story which I suggested splitting in two, and then I gave you some tips on how to develop other stories using some of the latent potential in the premise. A lot of writers don’t go through something like this. I’m glad you were game for it, though, because I feel like there are now some brilliant, quintessentially Michael Conley moments (the comfy-looking chairs in ‘Security Detail’, the tragicomic dilemma in ‘Personal Chef’) which wouldn’t have existed without that prodding. What was this experience like, from your side of the fence?

Exciting! I think as soon as we started talking about publishing with Splice, with your offer of very detailed and hands-on editing, I saw it as a huge opportunity to learn. The ‘Body Double’ stories were, like ‘Quetzalcoatl’, originally a series of poems, some of which I was happy with, some of which I wasn’t. But unlike ‘Quetzalcoatl’, they didn’t really work when I tried to bring them together, and they felt too fragmented. So your suggestion to just embrace that fragmentation and have them become a series of more free-standing, loosely-linked moments really worked, and unlocked lots more ideas. So much so that I’m probably not finished with that character and situation.

That’s good to hear! I feel like there’s more to be seen from that character, too. Speaking as a reader, I certainly hope so.

When I think back on that “hands-on” editing process, I realise that I was always anxious not to have those stories carrying my fingerprints. I wanted to help you bring things out of what was already there, rather than feeding things in. And indeed, when I read the ‘Body Double’ stories now, they don’t strike me as the sorts of stories I’d be inclined to write — or even the sorts of stories I could write — and I love them for that.

That’s ultimately what I mean about prodding: I felt like a guy at a jukebox machine, and I had an inkling that if I could just press a few of the brightest buttons, without really knowing what the results would be, maybe I’d cue up some killer tracks I’d never heard before. And it worked! But I definitely went into it first and foremost as a Michael Conley fan, not as an editor, just wondering how I could help the world receive a few more Michael Conley stories.

Does that ring true to you? Or are there moments in those stories where something doesn’t quite chime with you as a writer, where maybe I was treading on your toes?

I like the jukebox analogy, and I understand it, because I think basically you’ve just described what good teaching is. And what the best moments in the seminars I did at MMU were like. It’s not an easy thing to do, and not everybody is good at it, because it requires a lot of empathy to reach that deep level of understanding about what another writer is trying to achieve on their terms. And it also requires an ability to put aside ego. I think you did a great job of nudging me towards where these stories ended up. There really weren’t any moments at all where I felt you were taking over or pushing things in a direction I wasn’t happy with. So, thank you! Even if this book sells zero copies, I’ll feel I’ve come out of the whole editing process having learned a lot of valuable stuff about how writing works… although obviously I hope it sells tons of copies, too.

Don’t we all?

So the next batch of stories was the one where I began to get a bit jealous. These stories just started rolling out of you, one after another, needing comparatively minimal input from me, and it was clear that you were surfing one of those sustained waves of creativity that writers yearn for. Not only that, but you also seemed to be stretching your talents in all sorts of ways — these stories are the longer ones in Flare and Falter, more complex in their use of perspective and tense, and more varied in their tone and sentiments. There’s a sweetness to some of them, as well as darkness, and in ‘Kraken’ you’ve even got an apocalyptic story that actually works as a beautiful, satisfying romance, if you broaden your perspective as a reader to value more than the dramas of the (typically incompetent) human characters.

Can you talk a little about this period of writing? Satisfactions and frustrations? Unexpected successes and failed experiments?

Yes, those stories did seem to come quite quickly, and I did have a period of a few months where I felt like everything I saw and heard was a potential story idea, and then most of the ideas did turn into stories. There were really only a couple of ideas I had that didn’t develop: looking at my ‘Not Good Enough’ folder, there’s one where I tried to write something about the two characters in Auden’s poem ‘O what is that sound’, and I abandoned it because I realised they were too similar to the two characters in the bunker in ‘Personal Chef’. But other than that, yes, it was an unusual period where the hit rate was quite high.

I was watching these stories roll in and basically trying to take a step back, so as not to disrupt the flow or destabilise your creative energy. From my perspective, you knew how to wield your tools and the process became simpler. But I realise that this means I was, and am, blind to what you were doing behind the scenes. What was I missing?

I think having a full-time job plays a big part. I know not everybody is like this, but I’ve found I’ve always done my best writing at times when I’m busiest at work. (Although not literally at work, I should say.) I hardly write anything during half-term holidays. I’ve thought about why this is, and I think there are two reasons. Firstly, because during term-time, it’s a fast-moving and stressful job, so even when I’m at home in the evening, I’m in the ‘get stuff done’ mindset, and I think I’m lucky that I’m able to channel this into writing. Secondly, because I teach A-level English, which means I get to spend most of my working life having discussions with intelligent students about literature — so even when I’m not writing, the work I do feeds into my writing on some level.

How did that play out in terms of the labour of sitting down to write, and the trial-and-error process of it?

Nothing really beyond the usual process of writing the first draft quite quickly, then re-reading and editing more slowly, then sending it off. But I think it’s important not to romanticise that process, too. It does feel like riding a wave and it’s easy to see it as some sort of alchemy, but my feeling is that the truth is more mundane: it’s the direct result of lots of hard work and lots of hours spent reading and writing. I wrote ‘Kraken’, for example, very quickly in two short bursts, but I certainly couldn’t have done that if I hadn’t been writing steadily most days for the previous six months.

I want to come back to your role as a teacher in a moment, but for now I’d like to ask you about the final batch of stories you produced, which, in this case, is actually only one story: ‘All the Little Yous Just Find Each Other’. When you wrote this story and sent it to me, you said that it might be your favourite story of the whole lot.

I’m definitely really proud of that one.

I’ll tell you this now: it is my favourite, absolutely. How was the experience of writing this story different from writing the others? And what do you like about it?

As I mentioned earlier, the first spark for it came from the final line in a James Wright poem. The poem is called ‘A Blessing’. The tone of Wright’s poetry is so fascinatingly ambivalent, so he gives you this beautiful, romantic image, but it’s also confusing and out of the blue and bittersweet. I wanted to replicate that feeling over a longer story, using the same image as a central conceit.

I think perhaps the other, more unconscious influence, was Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas’, the first half of which is a description of a utopia. I fancied having a go at that, since a lot of the stories and poems I write are quite dark and often pessimistic. But then, like in the Le Guin story, there’s a kind of twist on that, too, in the second half, based on the idea of the price we pay for happiness.

I also just really enjoyed writing it: building the world, thinking of the odd little details that such a big change would throw up for people on a personal level. I had a lot of fun with the bit in the middle, another sort of twist, where we find out who the narrator of the story is. That allowed me to bring in uncertainty about everything that had come before and present a different side to the character of Grace, too.

Each of those elements works beautifully. For me, though, the real beauty of the story lies in the way all of them work together when really, in theory, they shouldn’t. They should clash almightily. There’s no sane world in which a story that starts off as an absurdist media satire can suddenly morph into something breathtakingly innocent, then morph again into an expository account of a utopia, then jump into a completely new mode of narration, and then conclude with a sustained passage of hypothetical, conditional action that is just so unremittingly dark but feels calmer and — like Wright’s poem — bittersweet. These things are so disparate that they shouldn’t be able to gel, and yet, well, the story speaks for itself.

You make it sound like the fun of writing it was almost a “Jackson Pollock splashing around with a bunch of different colours” type of experience. But did it ever feel like a high-wire act, like something that could end in chaos if just one element went awry? How much care and attention did you have to pay to balancing all these discordant things?

Hmmm. The honest answer is: not much. I hadn’t really looked at it that way, in terms of genre, when I was writing it, but I suppose when you step back and look at the story it is a strange mix of genres. Maybe a good analogy here is the coyote running until he realises he’s out of cliff, at which point he looks down and starts to fall. Maybe I was just running but I wasn’t aware I was running out of cliff, and somehow I managed to reach the other side because I didn’t look down?

One thing I’m interested in is taking a concept and then just continuing to pursue it until it’s exhausted. So, here, the concept was “now people can choose to burst into blossom”. I wanted to write the story until that concept became normal, and then see what happens. So it’s just as interesting to me that, say, people stopped throwing confetti at weddings in this world, or some people chose to continue being blossom as long as possible because it was better than being human.

I know I keep mentioning other writers, but a good example of this is, again, Lucy Corin’s 100 Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses, which is a collection of very short stories in which it’s already a given that the world is post-apocalyptic, so much so that it’s only ever mentioned in passing. So that’s what I was trying to do, and that’s probably why it ended up so chaotic.

I love that image of the coyote, and the story carries the feeling of his hopeful flight. It doesn’t seem like a work of random, directionless chaos, but of a very single-minded bolt towards a fantastic object in the distance. And I really have the sense that if you’d written a story like this in a workshop, for instance, every step of the way you would’ve been discouraged from doing all the different things the story does so seamlessly. You would’ve been told to look down into the gorge, and then you would’ve lost the momentum that propelled you.

Which brings me to my last couple of questions. You’re a teacher yourself. I imagine your classroom as a kind of a lively, animated, egalitarian forum with you sometimes in the middle, sometimes on the sidelines, in the role of Socrates. But what’s it really like? Can you give me a glimpse inside?

You’re talking about the chain-smoking Brazilian footballer, right? Lively, Socratic, animated, and egalitarian are all things I’d definitely aspire to, but you’d have to ask my students about how well that’s achieved day-to-day! But yes, I think they’d say that we do a lot of discussion and open questioning, and hopefully they’d also say that studying English is all about exploring ideas rather than getting definitively right or wrong answers. I’ve been a teacher for ten years and the best thing about it is still being in the classroom talking to people about books.

It’s a balancing act, often, because on the one hand it’s your responsibility to prepare students for exams, while on the other hand the whole point is that you want them to see literature not as a means to an end, but the end in itself, if that makes sense. There are things about the study of both language and literature that I find endlessly exciting, so ultimately all I’m trying to do is transmit that excitement to others. I’d consider it a failure if one of my students came out with an A grade but then never ever read a book or poem again in their life. I think that, as a society, we need the people who read to outnumber the people who think reading is a waste of time. And we need people who care about language and its intricacies, otherwise a president can get away with saying “would equals wouldn’t.”

Something I’ve noticed: in the author biographies in your previous publications, you’ve gone out of your way to put your teaching duties front and centre. How does teaching intersect with your creative practice and maybe influence the work you produce?

It’s a big part of my identity, full stop: I think the majority of teachers would say the same. Added to that, my partner is a teacher, and so is my sister, and so were my parents and their siblings. So I had no chance of escaping it even if I wanted to. The author biographies thing is a strange one: I hadn’t actually noticed I put that front and centre, but I guess I’ve been a teacher longer than I’ve been a writer, so if I’m going to reflexively identify as one thing, it will be that. Plus, it can feel presumptuous to write “Michael Conley is a poet…”

I’m not sure my experiences of teaching directly affect the work I’ve produced, in the sense that I’ve never written a poem or story about being in the classroom. But I think it does have an impact. One way, perhaps, is that there are several classic texts that I feel I know inside-out because I’ve taught them for years — Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, or Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles — and what I’m teaching with those texts is the deconstruction of methods: narrative perspective, plot arcs, characterisation, et cetera. There’s no way that this hasn’t helped me when I came to constructing my own stories.

About the Author

Michael Conley is a writer from Manchester. His poetry has appeared in various literary magazines, and has been Highly Commended in the Forward Prize. He has published two pamphlets: Aquarium, with Flarestack Poets, and More Weight, with Eyewear. His prose work has taken third place in the Bridport Prize and was shortlisted for the Manchester Fiction Prize.