Politics

by Thomas Chadwick

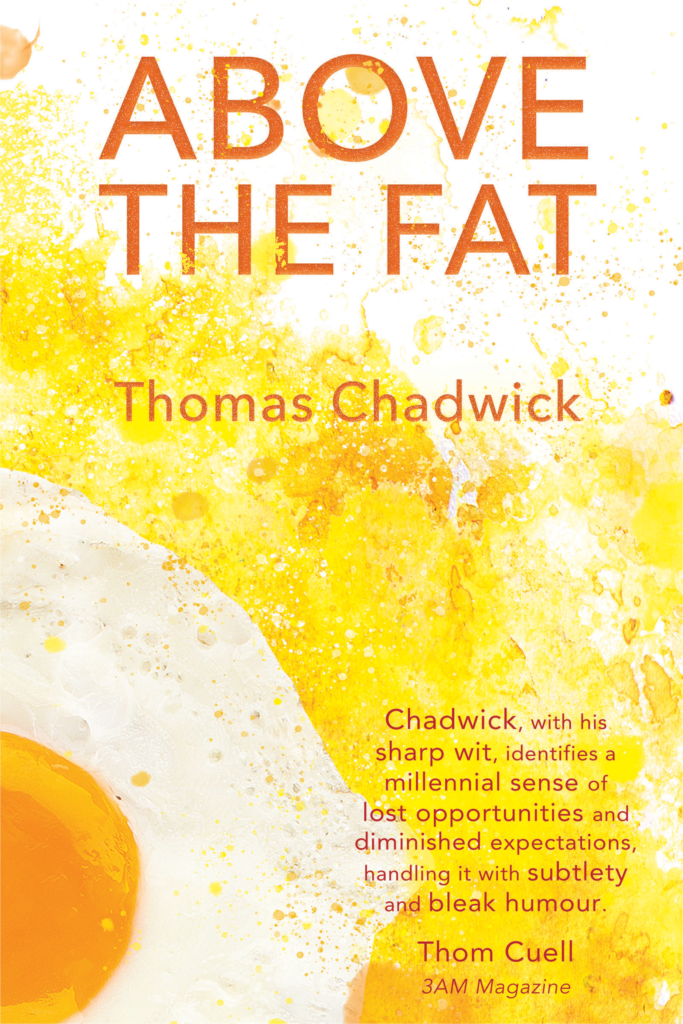

A new short story by Thomas Chadwick, author of Above the Fat, published exclusively online.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

David killed the Queen. It was nothing personal, he said. It was just politics. All he wanted was to make a political statement about the abuse of power in the country. After consideration, David had decided that power must be approached on its own terms. The terms of power — as everyone knows — are violence, and so David shot the queen in the back of the head from near enough point blank range. Above all David did not want to waste lives unnecessarily — violence can take indiscriminate forms — but killing the Queen, David argued, was a symbolic gesture. Besides, she was old. “Truth be told,” he said, “she didn’t even know who I was.”

The media of course were not content with the cut of David’s politics. They painted his grievances with the Queen as exclusively personal. He loathed the Queen, they wrote, he would vomit on stamps and pinned up over the walls of his room were images in which he had cut out her eyes.

“She’s a symbol! She’s a cipher!” David told the arresting officer. “She represents! All I want is a more representative democracy with a more accountable head of state.”

“Is this about proportional representation?” asked the officer.

“Damn right it’s about proportional representation,” said David. “It’s about us as citizens having our voices heard.”

Fragments of David’s statement were leaked to the press, twisted horribly and printed alongside an artist’s impression of the contents of his hard drive.

“What David forgets,” said an increasingly popular MP, “is that in this country we are not citizens but subjects.”

David’s classmates were unanimously shocked. The Queen had only been visiting their school to open a new science department and at that point few people knew anything about David’s politics. No-one expected him to step out of the line of spectators. No-one ever imagined he had a gun. “He couldn’t even bloody catch,” said a Geography teacher, who once took David for cricket.

One by one his peers were taken in for questioning.

“We got off once,” Kayleigh confessed. “On the coach on the way back from Germany. We weren’t close though. In fact, I hardly knew him at all. But I needed to get back at my ex for being such a dick in Berlin.”

“Nothing in his character to suggest he was born to kill?”

“On the coach he was playing Grand Theft Auto on his phone?”

Kayleigh was let off with a warning and urged to think carefully before launching into relationships with compromising men.

For History and Politics, David had sat beside a boy called Charles. “I wouldn’t say we got on,” Charles explained. “You see I, like most sensible people, believe in the benefits of free market capitalism. I think it’s the state that should be shrunk if enterprise is not to suffocate. I remain unconvinced about the long-term funding options for a National Health Service and I enjoy reading the novels of Ayn Rand. David, though, was, you know, a bit…”

“A bit?”

“You know, one of…”

“One of what?”

“One of them.”

“I’m not a socialist or a communist or an anarchist. I do not want a revolution on any scale. I simply want a democratic government and an elected head of state.”

“We have it on good authority that you’ve been reading the works of Karl Marx.”

“Who told you that?”

“We can’t say.”

“Was it Charles? Because if anyone needs locking up, it’s Charles. He thinks wealth trickles down. He knows all the verses of the national anthem. He sleeps beside a copy of Atlas Shrugged.”

David was told that for all his sins Charles had not shot the Queen.

Charles was released without charge. In a statement to the press — made in a full suit plus bowtie — he said he pitied David, whose politics were corrupted by naiveté and confusion. The increasingly popular MP said that Charles was an inspiration to us all in this time of despair. Later they would co-write a column for The Times.

David was beaten badly during his initial confinement. Patriotic members of law enforcement were bussed in from across the country and given the chance to wet their knuckles on David’s dimpled chin.

“Have you even met the Queen?” David spluttered through blood and broken teeth.

“No,” said PC Bold from Dudley, who was two years away from retirement. “But it’s the fucking principle of it.” After the state funeral the nation underwent a two-week period of mourning. In an attempt to outdo one another, newscasters would continue to dress in black deep into the following year and many members of the public declared they were unlikely to ever get over it. Meanwhile, an anarchist sect incinerated the science department the Queen had been on her way to open, proclaiming it a mark of respect for David.

“I’ve never even heard of the Socialist Workers Party,” David explained to his lawyer.

During the investigation, David’s politics teacher, Mr. Jarrett, was also arrested. The term prior to the Queen’s ill-fated visit to Kingsland Road Sixth Form College, Mr. Jarrett had taken the class through a political system that he himself — if pressed — would admit had some flaws.

“It’s the fucking syllabus,” Mr. Jarrett declared. “It’s not like I armed the boy.”

“That may be the case,” said the prosecution. “But the information you presented him with turned his mind into a ticking bomb.”

The court was shown David’s homework from the 14th October. It was a short essay entitled ‘For and Against the Institution of Hereditary Monarchy within the British Islles [sic]’, which would later become the prosecution’s most valuable evidence.

“That’s just homework,” Mr. Jarrett said. “It’s an exercise in critique: pros and cons.”

The prosecution said nothing. Using a laser-pen they drew the jury’s attention to the mark Mr. Jarrett had given the piece, an A-. Mr. Jarrett was given twenty years in prison for incitement to regicide and placed on the sex offenders register. “A storm of vitriolic resentment was stirred up in class U6B,” stated the press. “The fact that not more minds were swayed is testament to the indomitable spirit of English schoolchildren.”

In the weeks leading up to David’s own trial, daytime television and radio breakfast shows ran a series of call-ins that soon descended into a public brainstorm on methods of torture and slow death. “They should chop off his fingers,” said Mrs. Mathers, 57, from Newton Abbot, “and plunge his arms into salt.” The increasingly popular MP held a press conference on the first day of David’s trial in which he told the assembled journalists that “hanging would be too good for David Squires” — a statement that would turn a forthcoming by-election into a de facto referendum on capital punishment. Anarchist groups used David’s inevitable guilt as justification to march on parliament where they were met by a people’s militia formed that same day by two retired colonels from Godalming, determined to protect the legacy of their sovereign.

“Dead or alive, we will protect her,” explained a bloodied Michael Pewsey, 64, from Surrey. Midway through the trial it was estimated that over 45 million people had signed a condolence book that was making its way up and down the country.

For a few keen observers, it came as a surprise that it took until the third day of the trial for the defence to reference the Bible.

“The defendant is a deluded young man whose only crime was mistaking the Queen for his Goliath. His interest was to change a system, not destroy a life.”

The jury sat tight-lipped. In the stalls there were murmurs of disapproval. Meanwhile, after a coup, the increasingly popular MP used the fallout from the by-election to take control of his party and with it the reins of government.

“Above all,” he said in his acceptance speech from the street outside number 10, “we must be vigilant against those powers that would seek to divide us. We are but one people, beneath the rule of one Queen.” In the crowd people wept. In his first move as Prime Minister, the increasingly popular MP reintroduced National Service. Karen Beckett, 47, from Derbyshire was interviewed for the News at Ten and said she now felt safer at night.

In a short testimony given by video, David attempted to distance himself from the groups who had used his gesture as an excuse for more violence.

“I’ve been horribly misunderstood,” he pleaded. “It was nothing personal. It was just politics. I wanted to draw people’s attention to a slight flaw in our system, not force the nation to live under communism or kowtow to an anarchist sect.”

“What about your links with the Revolutionary Socialists?” the prosecution asked. David repeated his position that until the day of the trial he had never heard of any of these extremist groups. “I’m just a sixth former from Kent, trying to make a difference.”

The guilty verdict was unanimous. The judge gave David four consecutive life sentences, with the option to behead him if laws were changed. Up and down the country people turned to one another and said justice had been done. They continued to go about their business, to work, to raise families, to fall in love. At elections almost half the votes cast were not represented.

David drifted first from sight and then from memory. The last person to speak to him before he stopped receiving visitors altogether was a journalist for an online magazine. In a long exposé on David’s life in a maximum-security prison, the journalist explained that David was now a subdued man, his fervour gone. In fact, he had turned his back on politics altogether and was trying desperately to befriend his guards.

About the Author

Thomas Chadwick grew up in Wiltshire and now splits his time between London and Ghent. His stories have been shortlisted for the White Review Prize and the Galley Beggar Short Story Prize, as well as the Ambit Prize and the Bridport Prize. He is an editor of Hotel magazine.