Birch

by Thomas Chadwick

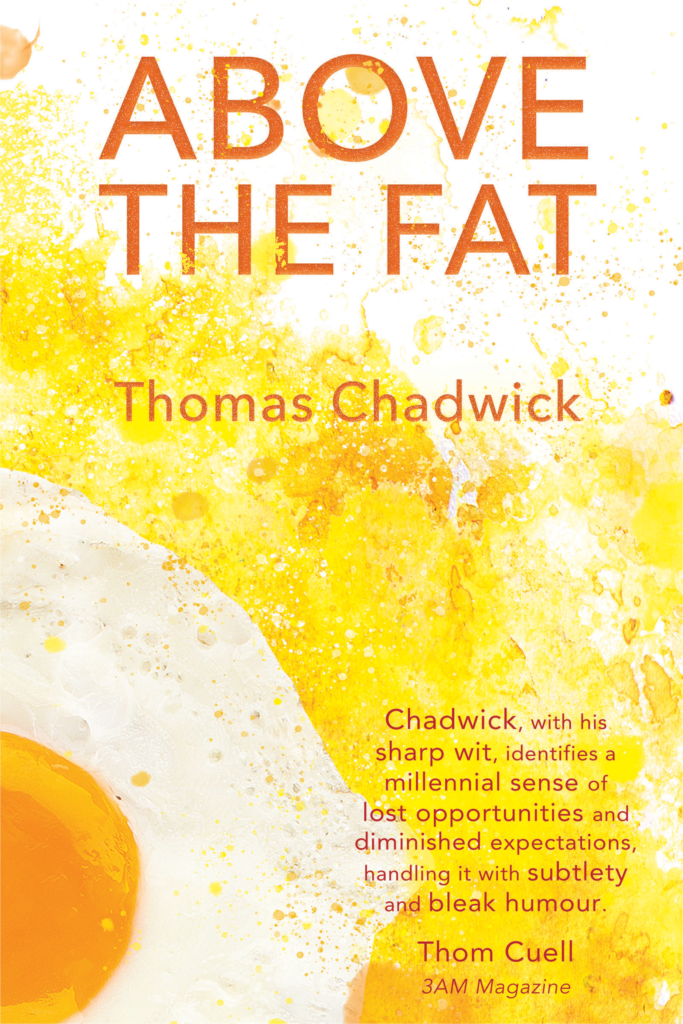

This story appears in Thomas Chadwick’s Above the Fat, available now from Splice.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

1997

Business boomed. Optimism was shooting up everywhere and bursting into flower. Music was jocular. Sport was effusive. Soon it would be possible to do the most wonderful things with computers. People woke and felt buoyant. Cereal was measured out with glee. Steam lifted from the mugs of recently reconciled marriages. Parents treated children to extravagant lunch box items. People would turn to their loved ones and say things like, “I can’t wait to read the paper” and “What a time to be alive.” But the people had been caught out before. They knew from history books and the Bible and Panorama that no flower can last forever; they knew that after summer the petals fold and fail, the leaves whither, the plant dies. The people knew that in good times smart people put down roots. So the people built houses.

People were building a whole lot of houses. To build houses you need timber and because Stuart’s business traded solely in timber the optimism soon wormed its way into the wood at Ford’s Mill. Orders were rampant. Builders bought four-by-two by the pack and skirting board by the bundle. Stuart sent his lorries out full every morning and watched them return empty by lunch. Often they would be sent out again because of all the fucking optimism about all the fucking houses; because business was booming and everyone was having such a great time; because it was all so serenely upbeat. “Education, education, education,” said New Labour. Smart people build houses.

Stuart was smart. Too smart to sell timber for a living, people said. Far too smart. Could have been a lawyer, they said. Could have been a damn fine lawyer. A teacher at Stuart’s school — Mr. Charters — had been certain that Stuart had it in him to be a damn fine lawyer.

“You should go to university,” he told Stuart, “and study law.”

“Dad wants me to join the family business.”

“What business is that?”

“The timber business.”

Everyone thought Stuart was making a huge mistake turning down the opportunity to be such a damn fine lawyer. “I never even got into law school,” he protested. Such a waste, they said. Stuart’s loyalties were at home. That was his problem. His loyalties. He was too damn loyal by half.

That spring, with optimism accumulating along rivers like froth, the foreman, Ted Coles, turned to Stuart and said he’d never seen the like. Ford’s Mill was an old-fashioned merchant, which meant it moved goods. The business bought timber in large volumes and sold it in smaller volumes. With the change in volume came a change in price. The change in price was the profit. Because the volumes were variable, so too was the difference in price and so too was the profit. The more timber they bought the cheaper the cost. The more they sold the more money they made. “It’s economies of scale,” Stuart’s Dad always said. To Stuart it was just common sense.

For years Ford’s Mill had been run by Stuart’s old man and his faith in economies of scale. Roughly a year after Stuart left school and started working for his Dad a competitor tried to buy them out. Representatives from Watt’s Timber Ltd. arrived in smart cars and pulled documents from a briefcase that said that if Stuart’s Dad gave them Ford’s Mill they would give him just shy of one million pounds. It was a substantial offer, the member of the acquisitions team explained, for the rights to the business and assets. Stuart’s Dad called Stuart into his wood-panelled office, with the oak table and plaque for Timber Merchant of the Year (Western Division) from 1986.

“I’m retiring,” he said. “This is as much your decision as mine.”

Stuart looked at the numbers and tried to picture what that much money would mean. “It’s just a few sheds and some timber? What do they know that we don’t?”

His Dad smiled. “That’s exactly what I was thinking.”

A few years later business burst into fucking flames.

By the summer of ’97, Stuart was buying obscene volumes of timber. Everyone agreed that currently the best timber was coming out of Sweden. At industry events Stuart would watch people lean across tables and say things like, “There’s some damn fine timber coming out of Sweden.” Stuart might have agreed but strictly speaking he had no say whether the timber at Ford’s Mill came from Sweden or Norway or anywhere else. Instead Stuart bought it from two wholesalers: one based in Hull, the other at Shoreham. His Dad had traded with Mitchall’s at Hull and Jennings’ at Shoreham since the ’70s. They did good deals. They were loyal. They were a far better bet than Peter’s at Harwich and Bamber’s at Portsmouth. Stuart’s old man knew Mr. Jennings and Mr. Mitchall personally and when Stuart started out in the industry he was introduced. Soon he, too, came to trust them. When his Dad died both firms sent flowers.

Construction is seasonal. Normally trade slows down in autumn and all but stops in winter. In ’97 no-one slowed down. Instead people saw a chance to get ahead. People were giddy with excitement and so said things like, “Fuck the frost let’s carry on building.” They hired heaters and lamps and kept at it. Stuart was getting through more wood than ever. Timber arrived on the racks in the morning and was out for delivery by lunch. He had to take someone on in the office to help Carol keep on top of the orders. Craig was fresh from Sixth Form. He wore glasses and was full of ideas.

“You should get computers,” he said.

Stuart laughed.

“I’m serious. They’d save time and paperwork.”

“We sell timber. Buy for a dollar, sell for a pound. We’re not putting men on the moon,” Stuart said.

Computers or no computers business persisted. Profits were large. Stuart’s wife planned a new kitchen. “Your Dad would have been so proud,” she said at breakfast, while eating their extravagant cereal.

I could have been a damn fine lawyer, thought Stuart.

The orders to Hull and Shoreham were non-stop. Both Mitchall and Jennings rang Stuart personally to tell him they’d never seen the like. “The way business is,” Jennings added. “You might as well take the whole boat.”

Really, thought Stuart, the whole boat.

That morning when the lorries were out for delivery, Stuart sat in the wood-panelled office at his Dad’s old oak desk and thought about what Jennings had said. He did some sums. He logged some costs. He asked himself how much of what he paid to Jennings found its way across the water to Sweden and how much stayed put in Shoreham. He wondered whether a smart person — someone who, say, might have been a damn fine lawyer had things been different — might make a different negotiation when business was this fucking good?

They’ve always done good deals out of Shoreham, he heard his Dad say.

But how do you know for sure when you’ve never tried to get better?

They’re good people. They’re loyal. That still counts for a lot in this business. We should stick with them. It’s common sense.

“It’s economies of fucking scale,” Stuart said.

Stuart asked around. He found a mill in Sweden that might deal direct. Not the biggest mill, but a moderate one with ambitions to grow. Everyone knows that business is all about growth. Stuart made the call from home, sat on their new bed, with the phone resting on the Egyptian cotton his wife had so thoughtfully picked out. The first time the phone rang the continental bleat vibrated inside Stuart’s skull and he thought he was going to be sick. The second time, someone picked up.

“Hello,” Stuart said.

“Ah, England,” she said.

Her name was Emma and it was possible. It was all possible. In fact Stuart should have been in touch a long time ago.

“Who do you deal with in Shoreham?”

“Jennings.”

“Well, Jennings has been — how do you say it in English? — ripping you off.”

Emma’s voice was fresh and warm and promising. She sounded like raindrops on new tiles; bare feet on warm gravel; a new wind through old leaves.

“Do you have a fax machine?” Stuart asked.

“We prefer email,” she said.

Stuart bought a computer. He placed an order. Timber arrived. The quality was high. The price was low. Housebuilders purred. New customers came. Fresh deals were struck. Beautiful lengths of timber passed through the gates at Ford’s Mill. Stuart would go out to touch them; to run a hand along their grain; to press his face against a knot and inhale the scent.

A letter arrived from Hull asking if everything was okay. Mr. Mitchall had noticed that Stuart had stopped placing orders. He knew that winter could be a tough time, but because of their strong relationship he would do anything he could to help out. As it happened, he’d been looking at Stuart’s terms on some core products and had decided that they could do better. Stuart rolled the letter into a ball and hurled it at the wall. The next day he did the same to a letter from Shoreham.

Stuart sat at the computer now installed on his father’s oak desk. His hands smelt pleasantly of pine as he tapped away at an email. Computers turned out to be easy. People made altogether too much fuss. But then Stuart was smart — a damn fine lawyer were it not for family loyalties. He finished the email and brushed the sawdust from his shirt sleeves. He hit send. It was all common sense with computers.

He thought often of Emma. They spoke from time to time on the phone. Stuart liked to hear the promise in her voice and the echo in her vowels. He wondered if she smelled like her timber. Once he asked her to describe the view from her window. She talked of sparse grass and tall trees, men in plaid shirts and hard hats.

“Can I come and visit?” Stuart said suddenly.

“The sawmill?”

“Yes. I’d like to see where the timber comes from, where the trees grow.”

“Yes, you should visit. But don’t come now. It’s winter. Everything is covered in snow. All I will be able to show you are things underneath snow and a mill where it gets dark before three. You will bring an insubstantial jacket. You might freeze to death. You will miss your wife. Come in spring.”

“How did you know I was married?”

“I do now,” she said.

1998

That spring business boomed. Wood was omniscient. Stuart could not get enough of it. He took on more staff. He bought two new lorries. He did a deal on some land with the neighbouring farmer and got planning permission to build a new warehouse. In April he flew out of Bristol. The sky was clear and the plane skidded down over pines, the trees densely packed along either side of the runway. In Stockholm his hotel was in Södermalm. On the first day he admired the Opera House and the park and the quayside. He visited a museum about coins. It grew cold. He bought a new coat. He ate cinnamon buns and drank coffee. He tried pickled fish and licked his lips. On the second day he took a boat trip out to the islands and marvelled at the clean lines of the landscape. He found a small cove and stood by the tide with the water lapping at his feet. On the third day he took a train.

Borlänge was only recently defrosted. Everything was made of wood and surrounded by trees. At the hotel Stuart was encouraged to sauna. He walked into a room of steam. He sat alone and sweated profusely. He thought of Emma. He felt light-headed. He was joined by a German businessman.

“I’m Dietmar, you must be here for the timber?” he said.

Dietmar discarded his towel. Through the steam, Stuart nodded.

“What’s timber doing in Germany?” he asked, in an attempt at conversation.

“Booming probably,” said Dietmar. “But I’m in paper so really I wouldn’t know.”

“Oh,” said Stuart. “What’s paper doing?”

“Paper is going fucking insane.”

Emma called the hotel to check that Stuart had found it. Her voice arrived dusted with nutmeg. She said the hotel would want Stuart to sauna. He told her he already had. She laughed. Stuart felt the receiver warm slightly against his check.

“Do you have dinner plans?” she asked.

“Not yet.”

“You will,” she said.

Stuart sat in the lobby until Dietmar convinced him to walk into town.

“But I have dinner plans.”

“It’s early,” Dietmar said. “We should go and look round.”

Dietmar was insistent. He was also angry. He had got into the paper trade at just the right time and he hated himself. “They are paying me so damn much,” he explained. “Even if I wanted to leave, I couldn’t. No-one can turn down the amount of money they are paying me. It’s criminal.”

“How much are they paying you?”

“So much, look there’s a bar.”

Dietmar insisted that they enter the bar. The only other customer was an old man in snow shoes. Over expensive drinks that he insisted on paying for, Dietmar explained that he wasn’t meant to be working in paper. He was meant to be a political journalist. “I come from a long line of devoted reporters. I studied at the Freie Universität in Berlin, I interned at Handelsblatt. But news was slow. I ended up in paper. I’m a huge disappointment to my family. They tell this joke at Christmas, I will try to translate: You were meant to be in the paper not in paper.”

Dietmar laughed hard across the empty bar. Stuart took a sip from his expensive beer.

“It’s not funny is it?” said Dietmar. “We should drink snaps?”

They drank snaps. Two of them, in quick succession. Stuart felt groggy. Dietmar enquired about a titty bar that had been recommended by a sales rep from Austria.

“That’s not really my thing,” Stuart said.

“My father spent four years as an undercover reporter. He exposed racism towards the Turkish community and the exploitation of steel workers. I am reduced to looking at Swedish tits before I visit a saw mill. My life is very sad. What were you meant to do with your life?”

“People used to say I’d make a good lawyer.”

“See. Our lives are tragic. My father was a wanted man for a time. He was given a medal last year for his vigilance. Let me buy you more snaps.”

They drank more snaps. The old man shuffled off in his snow shoes. The barman returned to say that there was no titty bar in Borlänge.

“This is bullshit,” Dietmar said. “Never trust a competitor.”

They left. Stuart tried to go back to the hotel, Dietmar said they couldn’t quit now: “Sometimes in the nice bars they lie about the nasty ones,” he said. They found a bar that advertised a Rage Against the Machine concert in Karlstad. Inside were several large Swedish men sat beneath beards and biker jackets and two very tall girls with blonde hair and leather trousers. Guns N’ Roses was playing on repeat. There was no snaps. Dietmar bought beers.

“I hate my job,” he explained. “It’s the least I can do.”

He tried to speak to the girls but they just laughed and said they were leaving. He asked the bearded Swedes about the titty bar he’d been told about by the sales rep from Austria. The Swedes just laughed.

“Are you here for the timber?” they asked.

“Yes, we’re here for the timber.”

They nodded. They said that they worked in the forest.

“What do you do there?” Stuart asked.

They laughed again and said they cut down trees. Stuart wanted very much to leave. Dietmar bought everyone drinks. “They pay me so goddamn much,” he said. “What do they expect?” At midnight Dietmar ordered a cab from which he stumbled to his room. The concierge stopped Stuart to say that someone called Emma had come by around seven. She had left a message to say that she was sorry to miss him and was looking forward to meeting him tomorrow.

Out loud, in the wood-panelled reception, Stuart swore. He drank water. He cleaned his teeth. He cursed. He decided it was not possible to call his wife. From the window of his room he could see a small hill where pine trees stood in silhouette against a moonlit sky.

Emma was tall and so blonde her hair was almost white. It glinted like frost as she shook Stuart’s hand in the lobby. She smiled and said nothing about dinner. Stuart was deeply in love.

“I see you met Dietmar,” she said.

She drove them out of the small town and into the trees. They drove through trees, past trees, around trees. Along one stretch of road the trees were so dense that you could not tell where one ended and the next began.

“I feel terrible,” said Dietmar from the backseat.

The sawmill was in a clearing. Emma worked in a wide-windowed office on the first floor where she offered them coffee. Dietmar drank his black with biscuits. From the window you could see sparse grass and tall trees, men in plaid shirts and hard hats. At a lightwood table Emma gave a short history of the mill.

It was founded by her grandfather in 1933. It grew rapidly after the Second World War and very soon established itself as an exporter to Europe. Her father took over in the ’70s and managed the mill until ’95 when Emma and her brother took over. Dietmar said it was a beautiful story and he needed more coffee. Emma pressed on with the tour.

Stuart met people. Swedish people with fair hair and broad smiles. He was given a hard hat and ear plugs and led into an enormous sawmill. He watched a tree arrive whole with its bark still on and leave in roughly sawn planks. Dietmar disappeared to the bathroom and then returned to bellow out questions about provenance. Stuart watched Emma’s hand as she led them out of the mill to the forest where trees would be ready in forty years’ time.

Stuart inhaled the scent of the forest, his bare face taut in the sunlight. Emma had changed into boots to show them the trees. Dietmar asked about lunch. He repeated that he hated his job and made further reference to how much he got paid. Emma walked through the pines, down a narrow path until the canopy disappeared and they were surrounded by birch. The trees were young, saplings, barely ten feet tall. Their bark peeled slightly from their trunks, branches shot out of clefts in their stems and up above the new leaves blushed pink in the morning sun.

“Do you have a canteen here?” Dietmar asked.

“You should pay attention,” Emma said. “We’re growing the birch especially for you.”

Dietmar said he was too cold and stomped his way back to the office.

“I called by the hotel,” Emma said.

Stuart stared into the silver branches. “Dietmar made me go drinking.” He stopped. “What did you mean you’re growing them specially for him?”

When a tree is cut for timber, it is divided into three separate products. The lower, central timber is the oldest and densest wood and thus of the highest quality. It is milled and planed and used for joinery and structural beams. The middle section, leading up to the branches, is used for carcassing and more general construction, lengths of 4×2, 6×2, 8×2 and so on. It is bundled into packs and sold to housebuilders. Everything else from the bark to the branches and twigs at the top is given over to paper and pulp. Some of it is ground up into sawdust or shavings and mixed with glue to make MDF or Stirling board, but most of it is used for paper. In Borlänge the separation of the products occurred in the sawmill. It was a seamless process. The lengths of timber were stacked on racks indoors awaiting delivery while the paper and pulp were bundled up and sold to people like Dietmar. He had only really come to see a byproduct. Maybe that was why he was angry.

“Dietmar is a huge problem,” Emma said as they walked through the birch. “Him and people like him keep demanding pulp. But the paper is not why we grow the trees. It takes over thirty years for a pine tree to reach a decent height, fifty for it to reach maturity. We can’t just cut them all down for paper. It’s unsustainable. So two years ago I planted this birch. It’s a new idea. My father thinks I am mad. A whole section of woodland devoted to birch! But others are doing it too. Birch is fast growing. In ten years it will be ready and we can chop it all down and turn it into paper.”

They were deep into the forest now, with birch as far as the eye could see; young limbs blistered in the late morning light.

“Besides,” said Emma. “They’re kind of pretty, don’t you think?”

“They’re beautiful,” Stuart said.

Back home Stuart made changes. He hired a sales team to ease the pressure on Carol and bought an integrated computer system that covered purchasing, sales, delivery, and stock. Craig was promoted to systems administrator and given his own office. He purred with delight. Only Carol remained unconvinced. “It cuts down paperwork,” Stuart said in a bid to persuade her.

But this was a lie. It did not.

Every time anything was done on a computer a printer leapt into action. There were four of them at Ford’s Mill: one in the sales office, one in the purchasing office, one in the yard office, one in Stuart’s office. They fizzed constantly throughout the day, churning out reams of paper framed by dotted edges that people ripped off and left scattered across the floor like confetti. The paper was carbonless copy paper that produced three identical sheets. This meant that the information could be divided between the office, the yard, and the customer. It also meant that every time anyone printed anything, whenever printers jammed or incorrect information was sent, the waste tripled.

The printers jammed all the time. Craig would be summoned to hunch over the ribbon and tease out the offending sheets. The waste went in the bin. The excess sheets went in the bin. Every day someone went round the office picking up the frayed edges and putting them in the bin. Sometimes, often when Stuart was least expecting it, the printer in his office would start spewing out paper for no reason — that paper also went in the bin.

Every week — sometimes twice a week — Stuart emailed Emma an order. He pictured her computer leaping into action by the window that looked out over the mill. He imagined her taking breaks during lunchtime and walking out through the thick snow, to stand in the midst of the birch. He remembered the way her hands moved as she explained about paper and pulp. He tried to think of things to add at the end of his emails: How’s your family? How’s your father? How’s your birch?

“Birch is good,” Emma wrote. “It is growing well. We hope to harvest in eight years, not ten, which is good because right now the paper mills are really squeezing production.”

Stuart had bought all the land between Ford’s Mill and the main road to make way for new racks of timber. The farmer who sold it to him also offered him the acres on the far side that led back towards the canal. It was just a field and a small copse where he would rear pheasants for city bankers to take the train down from London and shoot. It was not a large bit of land, but it was Stuart’s if he wanted it. Stuart decided he did.

In an email to Emma he sketched out his plan. He could fit several hundred trees into the acreage and in England, where the growing season was longer, they could be ready in just eight years’ time. “Dear Emma,” he wrote, “I’m getting into the birch game!”

Emma replied instantly. She was excited. They could compare notes. If Stuart’s grew quicker she would be jealous. Stuart smiled. His printer began spewing out paper.

“Are you building more sheds?” his wife asked later that evening.

“I’m going to plant birch trees.”

“Birch?”

“They use it to make paper.”

“Paper?”

She was confused. Stuart left the new extension before she could ask what his father would say or whether he’d thought it all though. Besides, he had thought it through. Paper was everywhere. With computers and emails and the web there was more printing than ever. Everyone was drowning in the stuff. And it was his mill now, not his father’s. He was making changes. He was shaking things up. Every generation had to betray the traditions of the previous one. That was common sense. And thus the birch, well, that was economies of scale. Yes, he’d thought it all through. Stuart was smart, remember; an almost lawyer, remember; and smart people made changes. They did not stand still.

“Paper?” his wife repeated later in bed.

Stuart rolled over.

“Isn’t everything going to be done by computers? Please be careful.”

“Careful of what?” Stuart cried.

His wife cowered behind the Egyptian cotton and muttered that they should think of the future. At one point she tried to take his hand. He threw it away and slept downstairs. The next morning a letter arrived from Shoreham to say that Mr. Jennings was dead.

“You should send flowers,” Stuart’s wife said.

The birch saplings arrived before Christmas when the ground was cracking with frost. There were hundreds of them. Small stems of silver wrapped in hessian. Five men came to do the planting. Stuart stayed to watch. Holes were dug. Trees were raised. Earth was moved. Roots were covered. By four o’clock everyone had left and Stuart was able to wander through the new trees as the sun set around them. The ground was compacted from where lorries had driven and people had stood. The trees were spread a few meters apart. Barely five feet tall. In ten years they’d be ready to harvest. “I thought you bought that land for a warehouse?” Carol asked from an office that was knee deep in paper. Stuart ignored the question and locked his door. Triplicate copies were piling up across the floor. He clambered over them until he reached the window and could look across the yard, through the street lamps that guarded the forklifts, towards the silhouettes of the birch.

Every morning Stuart walked across the timber yard and through the wide gate that separated the mill from the birch. He let Ted Coles take care of deliveries and spent time amidst his new trees. He felt their young branches. He ran his fingers over their blistering skin, felt shreds of bark muddy his fingertips. He wondered in what direction the new shoots would burst and whether there would be pink leaves next spring. A few of the trees did not take and died where they sat in the soil. Tears ran down Stuart’s face as he removed the branches and burnt them. He buried the roots where they lay. In the evenings he would sit on the thin grass that grew up beneath the trees and listen to the sound of the wind. His wife was pregnant now. The baby was due in June.

That May, Stuart received a complaint. A phone call was put through to his office from a man called Keith. Keith was head of purchasing at a big housebuilding firm in the west. He said he would have to be blunt.

“The timber you’ve been sending has been a load of crap. The wood’s all wet and warped and the quality is low.”

Stuart apologised. It was an oversight. A mistake. There would be a full refund and the promise never to do so again. Stuart would see to it personally that this was never repeated.

“I appreciate that,” said Keith.

Printers leapt to work to correct the oversight. Emergency deliveries were made. A week later another complaint arrived from a man named Mark. Then from Joe. Then Steven.

“It’s Sweden,” Ted Coles explained. “They’re sending us lousy wood.”

Stuart shook his head. That night he sat for a long time amidst the birch. He listened to rooks crowing as they came in to roost along the canal, cawing at one another as they negotiated their perches. It was dark by the time he got home.

After three weeks of complaints, Stuart called Emma.

“Stuart! How’s your birch?”

“Beautiful, how is yours?”

“Slow. Far too slow.”

Stuart explained about the problems with quality. Emma apologised. It was the paper, she said. Between friends, it was all because of the fucking paper. Orders were off the scale. They had harvested too many trees the year before. More trees than they could fit in their sheds. Some of the wood had been stood outside over winter beneath tarpaulins. “We invested in the very best tarpaulin,” Emma explained, “but the very best tarpaulin is no match for Swedish snow.” Anyway, this was beside the point. Stuart should not have been sold the timber left outside. As a valued customer, as a friend, he should have been sold the timber from indoors. Emma apologised. It was an oversight. A mistake. There would be a full refund and the promise never to do so again. Emma would see to it personally that this was never repeated.

“Anyway,” she said, “I hear congratulations are in order.”

The next load of timber that arrived at Ford’s Mill was the worst Ted Coles had ever seen. He sent it all back and sulked in the delivery office. Emma was not in when Stuart rang. A sales clerk cut the price on the phone. Stuart cut his prices. Printers whirred. Keith emailed to say that he was switching suppliers. Mark said the same. Most people just stopped placing orders. Timber stood still on racks. Piles of grey wood lay propped up in mounds, beside the paper that Stuart did not know how to recycle. The baby was due in a month. The birch was seven feet tall.

Shortly before his son was born, Stuart rang Shoreham.

“I was sorry to hear about your old man, I have this horrible feeling I forgot to send flowers.”

“My old man?”

“Your father, Mr. Jennings?”

“You’ve got the wrong bloke. Bob Jennings’ son sold up first chance he could. We’re owned by Peter’s & Bamber’s now.”

The sales manager, whose name Stuart missed, was sympathetic. He listened attentively. He knew about all the problems in Sweden. It wasn’t just Sweden, though. Everywhere had harvested their forests to keep up with the paper. “There are stacks of timber slowly rotting across the whole of northern Europe,” the sales manager said. It was a struggle for quality all round, but Stuart was lucky he’d called when he did. “There’s a lot of clout up here after the merger. We’ve been able to squeeze the mills to get the good stock, but it comes at a price.”

Stuart was quoted a figure that was almost double what he’d been paying Emma at Borlänge. In truth there was no real choice. It did not matter that the timber was good. Responses were blunt. Phones were placed on receivers. Memories were short. Sales fell. Printers jammed. Wood wasted away on the racks. Stuart’s son screamed all night and in the day the forklifts lay silent. Craig left to take a job in IT. Carol retired. Ted Coles said he’d never seen the like. The paper was taken away by the council in a lorry that cost Stuart four hundred pounds. The birch reached shoulder height. Stuart spent whole days there now, walking through the trees, touching them, caressing their leaves, wondering if he would ever have the heart to fell them.

1999

Business slowed. Business stalled. Business fell off a fucking cliff. The delegation from Watts’ Timber — which included two directors, the regional operations director, and, in order to try and push it all through that same day, the Chairman, Peter Watts, himself — stepped out of Stuart’s wood-panelled office and examined the site at Ford’s Mill. Watts’ Timber had been hit by the slump, just like everyone else, but Mr. Watts knew that only those operations that stood still would flounder. As soon as signs of a downturn were felt he set about buying up those sites and businesses that blocked the stability of his market share. Often, as was the case with Ford’s Mill, Mr. Watts had tried to buy these sites and businesses before. Mr. Watts had always been surprised that old Mr. Ford would not give in, but he’d assumed that Stuart would have no interest in timber.

Unlike many of the sites Mr. Watts had purchased that week, where the businesses would be dismantled and the land sold on at a profit, Ford’s Mill was, in fact, an enviable location. Stuart, who sat mute in the office as his lawyer examined the paperwork, had acted prudently in the intervening decade. He had bought more land and had planning permission approved to build a new warehouse. There were good staff by all accounts and an integrated computer system, which would allow Stuart’s stock to become Mr. Watts’ stock with nothing but the click of a button. Yet despite all these changes, Mr. Watts did not need to see an account ledger to know that all was not well. A business that grew this fast could not hope to survive unless it put down some roots. As soon as Mr. Watts got word that Ford’s Mill was struggling — through Peter’s & Bamber’s, as it turned out — he got his acquisitions team to start work on an offer. At first Stuart refused, just as his father had refused ten years earlier. Mr. Watts listened. He took note of the expansion and the extra sheds. He increased his price. Stuart wavered. The price was increased one final time and Mr. Watts was driven down to Ford’s Mill to sign the paperwork in person. He did not mind the excursion. He liked buying things and he had an aunt who lived nearby who was old and who he intended to visit. He would drop in after he’d inspected the mill and enjoy a cup of tea. It was important to take time for one’s family. Peter Watts said as much to Stuart earlier in the office where old Mr. Ford had once refused to sell the business but where Stuart was now only too glad.

“I understand you have a young son,” Peter Watts said.

Stuart said nothing and stared at the wall.

The delegation walked past the timber sheds towards the outdoor racks where the forklifts and summer rain had turned the ground into mud. Ever astute, Mr. Watts caught sight of the gate that led through to the birch trees in the adjacent lot.

“Do we know who owns that?”

“It belongs to the mill.”

Peter Watts sounded surprised. “Some conservation project, I suppose. It’s good land. We can use it.”

“Actually,” said the man from the acquisitions team, “it still belongs to the mill.”

“Why do we not own it?”

“He refused to sell. We offered more money, but he wouldn’t listen. It’s only a few trees. It’s worth nothing on its own. I’m not even sure what they are.”

“We couldn’t figure out why he hadn’t built more sheds,” another member of the acquisitions team said. “There’s planning permission and with the amount of timber that’s been left out in the open it would have made far more sense to build cover.”

Peter Watts snarled as Stuart emerged from the office and made his way across the yard. He did not look towards the group of men in suits. Instead he walked right past them, lifting his legs through the stolid mud in the direction of the gate. When he reached it he lifted his leg onto the bar and vaulted onto the other side. Without breaking stride he continued walking, through the birch trees, past the silver skins that grew so swiftly in the sweet Stanton silt, until at some point the blushing leaves enveloped him and he disappeared from sight.

About the Author

Thomas Chadwick grew up in Wiltshire and now splits his time between London and Ghent. His stories have been shortlisted for the White Review Prize and the Galley Beggar Short Story Prize, as well as the Ambit Prize and the Bridport Prize. He is an editor of Hotel magazine.