“I have felt the impact of the dive”

by Anna MacDonald

This text is excerpted from Anna MacDonald’s début novel,

A Jealous Tide, available now from Splice.

Hardback: £14.99

Paperback: £9.99

In the beginning the water felt strange. My body registered it as a change of temperature more than a shift out of one element, into another. But the warmth had a soothing effect on my flight-cramped muscles. It steamed open my pores and moment by moment returned the moisture to the liquid layer beneath my skin. Lying back against the sloping porcelain rim, I looked up through the skylight and watched the vapour trails of other flight paths leave rippled sandbanks against the sky like a sea tide on the ebb.

Later, I walked out of the house and into the afternoon. I moved quickly back down Rowan toward Hammersmith Bridge Road, and on to the river. Away from the nucleus of the station with its radiating A-roads, away from its memory of another, underground world. Fresh from my bath, the ground felt unnaturally rigid beneath my feet, which slapped awkwardly against the pavement where they should have moulded to its contours, made a bridge over its many cracks: heel, the bubble beneath the arch, five spread toes, then repeat. But as I walked and slowly learned my surroundings anew, noting familiar landmarks, taking stock of neighbourhood and seasonal changes, I felt my legs loosen. My hip joints regained their limber. My feet trod firmly across the ground.

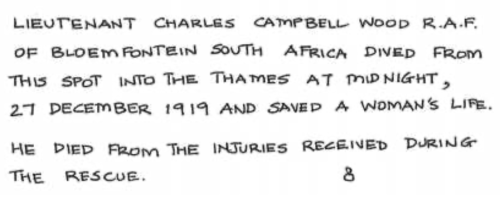

These are the habits of travel: arrive, unpack, bathe, then walk down to the river. Crossing the bridge, I paused as usual to read the plaque to Lieutenant Charles Campbell Wood and the unnamed woman, and look from it into the water. I had first noticed the plaque several years before. On the upstream balustrade, near the mid-point of the bridge, it lies flat to the timber rail with the slightly puckered appearance of a successful skin graft after it’s healed. Its horizontal stretchmarks align with the railing’s timber grain, visible where the paint has peeled in the weather that rolls downriver.

During that earlier visit, on clear summer mornings, I liked to take my coffee to the south side of the river, to sit beneath the trees along the riverbank and watch the tide run out. Bounding dogs snuffled mud puddles along the towpath. Cyclists and early morning joggers left spatter patterns of river muck up the invisible seams of their lycraed legs, along their knobbled spines. Once, a young man with the single-minded, inward stare of a hillwalker strode past in the direction of Putney. He was kitted out with a new rucksack, which he’d packed carefully. His compass was tied to an external canvas strap, positioned within easy reach. It slapped against his back, keeping time with the rhythm of his heavy-booted step.

It was my habit that summer to walk out along the downstream side of Hammersmith Bridge, and back along its upstream path. Returning one day, I happened to pause by the balustrade, to look down at the puckered plaque and read:

Midnight. A precise and evocative time. A moment of transformation that marks the death of enchantment. 27 December. So close to Christmas, when the water would have been unforgivably cold. 1919. The cruelty that a man who survived the First World War should lose his life almost immediately after it, in the wake of his family’s relief, believing him to be safe, awaiting demobilisation and the journey home. The southern, watery echo of Bloemfontein. Wood’s rank, full name, and place of birth alongside the anonymity of the unnamed woman. The saved life of someone unknown. And the postscript—that lonely figure 8—a fattened infinity symbol, like an icon for a healthy body, a figure that cradles within it the promise of another life. I’ve scoured the plaque for the ghost of some further engraved line, thinking that this could indicate the date of Lieutenant Wood’s death. But if there was one, once, I can’t find it now. And so the 8 appears to hang there, neither belonging to the lieutenant and the unnamed woman he saved, nor wholly alien to them.

On that warm summer morning when I first looked from the plaque down into the water, and often since then, I have conjured images from the precise wording and evocative silences of the brass. I have imagined the urgent arc of the lieutenant’s dive from the bridge balustrade and wondered if he stopped first to remove his boots, to shrug off his British Warm coat and doff his RAF cap. I have felt the impact of the dive, crackling with cold, and the reverberating force of river water along finger bones, gaining momentum within the rapid inward spiral of the inner ear, following the rutted road of a war-eroded spine. I have imagined the safety of shock, the lieutenant snug inside the exertion of action—launching into the water, lashing out in long strokes towards the drowning woman, trawling her behind him in to shore. And, on the awkward pebbledash of the northern bank, in the mud and refuse of the city, I have imagined a resuscitation. I have heard the woman’s first caught, water-clogged breath. Then, in the aftermath of action, I have discovered in the heavy-breathing quiet the lieutenant’s growing awareness of catches within his own body, of bones perhaps out of alignment, organs slightly out of place. I have felt the liquid space beneath the skin. And I have wondered about the woman, still and always unnamed. If she quietly thanked the lieutenant for his effort. Or if she lay on the bank, feeling the city’s discarded and otherwise abandoned wrack dig into her twisted hips, catch in the tangle of her waterlogged hair, and despairing, at two lives, now both lost.

About the Author

Anna MacDonald is a writer and bookseller based in Melbourne, Australia, and a Splice masthead contributor. She has previously reviewed for 3:AM Magazine and the Sydney Review of Books, and she also writes for the Australian Book Review. Her collection of essays, Between the Word and the World, was published by Splice in 2019.