Pinniped

by Michael Conley

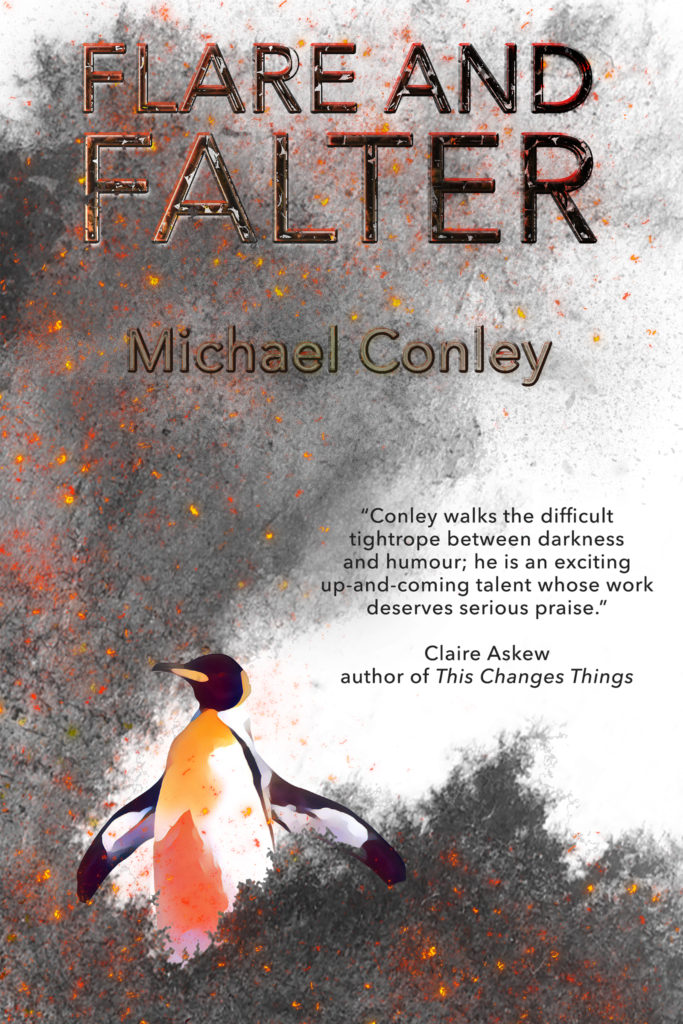

This story appears in Michael Conley’s Flare and Falter, available now from Splice.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

We know they must smell like the dustbins behind a seafood restaurant, although we can’t smell them from here. They look as cold and alien to the touch as the part of your leg that finds its way out from under the bedclothes in winter. They look like, if you slapped them with an open hand, it would make an echoing clap, and the flesh would continue wobbling for a significant amount of time afterwards. They are surprisingly rough with one another when it comes to defending the prime basking spots on the floating wooden pallets in the harbour. Their low call is the cri de cœur an unhappy stomach would make if it could talk.

The seals are a new addition to the attractions on the seafront. There are five of them. People are crowding the railings at the quayside to get a look. We’ve been here for twenty minutes in the cold. I stand behind Kerry. She takes my hands and drapes my arms over her shoulders like she’s fastening a cape. I bury my nose in her hair. I’ve never seen her like this: she’s breathless, commentating on everything the seals are doing as if they were her own beloved children. “Look at that one! You don’t like being shoved, do you?” “Awww, they’re not letting that little one sit with them!” “They can stay underwater for ages, can’t they?” She’s talking to me but she’d probably be saying exactly the same things if she were watching them by herself.

Later, in bed, even though we haven’t been talking about the seals, she asks whether I think they feel frustrated without any arms and legs.

“It makes them better swimmers,” I reply, after a moment’s thought.

“No,” says Kerry, “I mean when they’re out of the water. Like when you see them on those wooden pallets and they’re shuffling up and down, and they have to crawl on top of each other to get into new positions, I bet they’re thinking, ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, this is so annoying!’”

“I like it when they get half onto the pallet, but there’s not enough room, so they just kind of slowly slide back into the water. Reminds me of someone chucking out a full binbag. But no, I don’t think they’re bothered.”

“I think they are. It’d be like someone locking you in a sleeping bag and saying, ‘Right, this is how you move now, this is how you interact with others, and it takes ages to do everything.’ You’d be annoyed about that.”

“Yeah, okay,” I concede, “I might be annoyed, but don’t forget they’ve never known what it’s like to have arms and legs.”

“They’re always having a go at each other, too. Roaring at each other. Barking, whatnot.”

“You think they’re irritable because they don’t have arms and legs?”

“Could be.”

“But what about birds? Do you think they look at us and say, ‘Humans must be so frustrated not being able to fly; maybe that’s why they have all those wars’?”

It’s dark, and I can’t see Kerry’s expression. I get the feeling I haven’t provided the answer she was fishing for. She turns over onto her side and falls asleep before I do.

The seals aren’t far from our apartment. We’ve been to look at them enough times that Kerry has named them all. Aside from the largest, Big Daddy, I’m not always sure how she differentiates one from another. Most of the time, when she’s commentating, I’m not sure which is which. Of course I don’t admit this to her.

After Big Daddy, the second-largest seal is, as a logical follow-on, Big Mama. Kerry must’ve done some research into how to spot the gender differences.

I got no say in the naming, even when I begged to be allowed to name at least the smallest one. My first suggestion was “Henry Olusegun Adeola Samuel,” the real name of the singer Seal. My second suggestion was “Les Sealey,” after the former West Ham and Manchester United goalkeeper. Kerry wasn’t amused by either, perhaps rightly so, and I gave up trying to think of more.

Big Daddy, generally, is the only one guaranteed a place on the wooden pallets. The others don’t even challenge him. Sometimes one of the three smallest seals, Kurt or Biff or Darlene, will have been asleep and immobile for what seems like hours, but as soon as Big Daddy’s whiskered malteser of a head periscopes up from the grey water, they spring to life like electrocuted teenagers and make room for the alpha.

I suppose I first realise something is a bit amiss when Kerry mentions in passing that she has rejigged her entire scheme of work for this term so that her Year 4 class can learn about seals. She tells me that a parent has complained about the large volume of maritime-related activities assigned to her daughter: geography homework on Alaska and San Francisco, history lessons on transatlantic whaling, literature extracts from Moby-Dick. The complaint was triggered by a permission slip for a fifth field trip Kerry had planned to our regular spot by the railings — DURATION: ALL DAY. Kerry countered with a trusty retort (“Well, more than anything, I’m disappointed that you’d question my professionalism”) and the parent backed down, but not without having stirred in Kerry something I couldn’t quite put a name to.

She’s been spending long evening hours in the bath. One time, even though I knew I shouldn’t have done it, I stood at the door and held it open just a crack and peered in. I found her practising holding her breath. She was incredible at it. I counted the passing seconds in my head, kept counting as the seconds became minutes, gave up when I lost track of the time. Now, more often than not, she crawls into bed without having dried her hair. She leaves wet patches on the pillows. They seem to get colder and damper as the nights progress.

We’re browsing our smartphones on the sofa one evening, only half-watching the TV, when suddenly Kerry lets out a squeal. One of today’s Snapchat filters turns her into a cartoon seal with glassy black eyes and chubby, whiskered cheeks. She takes several selfies, a few snapshots of me, and lastly a picture of the two of us: she hangs an arm around my shoulders and our faces almost touch. Then she posts this picture to her timeline with the caption “Big Daddy & Big Mama” and three crying-laughing emojis. We spend a couple of hours on a loud contest of who can make the most accurate seal noise. It’s somehow better if you flap your hands like flippers while you’re doing it. It’s a mixture of a growl, a bark and a honk, and you have to finesse it. You have to gulp a pocket of air and hold it in the back of your throat. We decide that if it turns into Kenneth Williams making the “matron” sound, you’ve gone too far with it. If it sounds like Alan Rickman as the Sherriff of Nottingham, sighing at the stupidity of a disposable underling, you’ve not gone far enough. Both of us claim victory.

The final time we have sex, she slips into bed without having dried herself at all after her bath.

“Go with it,” she whispers, touching my face gently and kissing the corner of my mouth.

She produces the cord from my dressing gown and ties my legs together just above the knees. She does the same to her own knees, with her own dressing gown cord, and then lies on top of me, facing up. Her arms, by her sides, are rigid.

One Monday morning, I miss the alarm and am horribly late for work. Just as I’m leaving the house, Kerry’s headteacher calls. She tactfully points out that the doctor’s note for Kerry’s two-week leave of absence has expired today, but she has not heard anything from Kerry. Of course I have no idea about the leave of absence, but I make a hasty excuse, saying she’s in the hospital, and then I apologise profusely for the mix-up. The headteacher immediately becomes concerned and asks me what’s wrong, did something happen, is everything all right, so I decide the best option is vagueness, delivered gravely. I mumble something about inconclusive tests. The headteacher says she’s sorry and assures me that the supply staff will be retained and before she hangs up she makes me promise I’ll keep her informed.

When Kerry arrives home, we argue. I confront her and ask her straight-up where she’s been going for the last two weeks. At first she doesn’t answer. Then I ask her whether she’s been having an affair. She snorts and tells me it’s just like me to think that’s what she’d be up to. Abruptly she packs a bag and leaves.

When she doesn’t come home the next day, or the next, I phone the headteacher, angry, and I say that Kerry has moved away and won’t be coming back. The headteacher asks for a forwarding address. I hang up and block the number.

I see it first as a viral video, when several notifications at once ping into my phone: “OMG isn’t this right near u?”, et cetera. In the shaky, grainy footage, a figure slithers under the railings at our regular spot and slips gracefully into the sea. There are screams from onlookers, and the amateur cameraman rushes to where the figure plunged in, scanning the surface of the water. Finally, after what feels like too long, Kerry appears by the pallets. Where did she find a grey speckled wetsuit with a mermaid-tail bottom half and no armholes? To gasps and laughter from the people on the pier, she rises from the water and pitches herself headlong onto one of the pallets, right beside where one of the smaller seals — I think it’s Darlene — is lounging about indifferently. Two, three, four times, Kerry only manages to get the top half of her body over the side before she slides back into the water. The fifth time, she manages to stay on. The audience applauds as she flops down, exhausted, her head against the wet wood. Darlene rolls over and the two of them huddle together, their long straight bodies pressed against each other from head to tail.

The camera zooms in, but the face is too pixellated for anyone to identify her, I think.

The video ends up on the local news that night. Later in the week, the national news. The media sticks with the story for a while, christens her “Seal Girl,” but because she never speaks and always stays down there by the pallets, nobody knows who she is or where she might have come from. Her wetsuit includes a hood like a cross between a bathing cap and a balaclava, and it pushes her cheeks in, distorting her face. A journalist ventures out in a speedboat to see if he can score an interview, but when the boat draws near to Kerry she disappears into the water along with all the other seals.

There’s general confusion about how she survives. Some people swear they’ve seen her eating raw fish quite happily. Some throw food at her, believing she’ll settle for scraps to fill her belly. Some start selling unofficial Seal Girl memorabilia around the pier; some insist, untruthfully, that a percentage of profits goes towards ensuring her health and safety. As for the seals, she seems to be wary only of Big Daddy, taking the lead from the smaller ones about how to stay out of his way when he starts to bellow.

Eventually, months later, when there are countless videos of her online and even more poorly-written comments calling her so many ugly names, I’m woken at night by the slap of bare feet on kitchen tiles. When I come downstairs I find the wetsuit folded, dripping, over the back of a chair, and there’s Kerry sitting naked at the kitchen table. She’s trying to pluck an apple from the fruit bowl. Was it the hunger that got to her in the end, that pulled her from the waves and brought her back to me? Her grip is so weak that the apple falls onto the floor and she looks at her arms in bewilderment, as though she’s only just been given them. There are dark bruises up and down the length of her thighs and on her shoulders. Her cheeks, nose, and forehead, exposed to the elements for so long, are red and flaking and swollen.

Kerry looks up to find me standing in the doorway and opens her mouth to speak. When words fail to escape her lips, she lurches forward and hobbles to me and drops herself into my embrace. I hesitate to hold her at first, but then I clasp her tightly to me and I place a gentle kiss atop her head. My nose in her hair, drawing in breath, I notice how she still carries the smell and taste of the sea: fresh, salty, too strong.

About the Author

Michael Conley is a writer from Manchester. His poetry has appeared in various literary magazines, and has been Highly Commended in the Forward Prize. He has published two pamphlets: Aquarium, with Flarestack Poets, and More Weight, with Eyewear. His prose work has taken third place in the Bridport Prize and was shortlisted for the Manchester Fiction Prize.